What were the real needs for a « Reformation » ?

The wish to reform the Church had appeared on many previous occasions, but in the early XVIth century it was very widespread throughout Europe. However no consensus could be found concerning the principles and orientations of a reformation. Three trends could nevertheless be defined.

- Reformism considered that the principles of the Catholic Church were good, but not correctly implemented. The aim was to correct abuses and errors, but not to break away from the Church. Reformism partly reached its aim with the amendments adopted at the Council of Trent – referred to as the « counter-reformation » since it reacted against the Protestant reforms ; however it also implied a true « catholic reformation ».

- The so-called « magisterial » reformation relied on governments, princes or city councils (referred to as “magistrates”), and likewise on professors of theology whose role was of great importance. It was made up of two main trends : Lutheran and Reformed. Its aim was to correct not only the practices of the Church, but also its principles by eliminating or amending whatever was against the teachings of the New Testament and maintaining the rest. There aim was not to establish a new Church, but to thoroughly change the existing Church. Rome refused and the unwanted breach became inevitable.

- The so-called « Radical » reformation – so-called because it esteemed that the Lutherans and the Reformed did not go far enough – but stopped reforms half-way. It was characterised by :

- Anabaptism (refusing child baptism)

- illuminism (proclaiming that the Holy Spirit speaks directly to the hearts and minds of true believers),

- and anti-trinitarianism (denying the dogma of the Trinity, considered as being non-biblical).

The Radical Reformation did not want to maintain anything of the Church. Its purpose was to follow the apostolic model, to create the Church of the New Testament by eradicating the heritage of past centuries.

Lutherans and Reformed both claimed that anything not forbidden on a biblical basis was allowed. For the Radicals, anything that was not expressly ordered was forbidden.

God alone is God

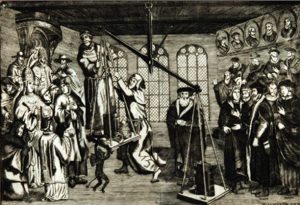

Protestant reforms accused Catholicism of not making insufficient differentiation between the Creator and his creatures and of giving a « holy » status to some of the latter. The conviction common to all Christians that « God alone is God » meant for the Protestants that God alone is holy, and that no other person or object deserved to be revered and adored. Such a rejection of all sacralisation was manifested in various ways.

- The Reformed and the Radicals, in a more determined way than the Lutherans, refused to consider the bread and the wine of the Lord’s Supper (or Eucharist) as corpus Dei or the true body of God. They are signs, and not elements that assume a divine nature by a miraculous transformation.

- No Protestant movement accepted « saints », even biblical, who had to be revered and called upon during traditional Christian services and prayers. The key words Soli Deo Gloria (glory be to God alone) meant that He alone should be worshipped and adored.

- All Protestant movements denied the existence of a clergy set apart by consecration, of a status superior to other worshippers and implying their compulsory role as mediators between God and man. According to the priesthood of all believers, all Christians have equal access to God. Some Radicals even refused institutionalised clergy such as priests or pastors. Lutherans and Reformed had « ministers » (servants) with specific responsibilities such as preaching and teaching, but with no specific religious status.

- All Protestant movements were very wary of the sacralisation of the ecclesiastical establishment. If such an institution was necessary for the community life of Christians, it was neither infallible nor perfect. It had to be permanently open to amendment and purification. The Church is semper reformanda it is always to be reformed.

Free salvation

All Churches proclaimed that no one can be saved as a result of his own efforts or virtues, but that God grants free salvation through his mercy alone and not by merit. The term « free » was common to all churches, though each gave it a different meaning and scope.

- For most Catholics God asked man to make efforts, and granted his salvation to « men of good will ». Man is not worthy of it, but must prove that he longs for it. God endows man with what he lacks. Salvation concerns the future ; it crowns a life in which the gift of God takes human circumstances into account.

- Lutheranism generally considered human thoughts, aspirations, and actions as evil. Though they might be morally acceptable, they had no spiritual value. God grants his salvation and demands nothing in return ; every believer is at every moment a forgiven sinner while remaining a worthless sinner, and forever benefits from God’s unconditional love manifested in Christ.

- Salvation is a daily experience. Everyday God grants it again to the believer, as if it were the first time. The Reformed on the whole considered salvation as something belonging to the past. God had pronounced it even before the creation of the world and manifested it through Christ. The believer receives it though he does not deserve it. God granted it to him before he was born and would not take it away. A man’s life is not a matter of obtaining salvation, but of witnessing to God and worshipping Him in this world.

Some Radicals claimed that a believer should totally eradicate sin from his life and thus become perfect. For the Reformed, even if a Christian realises the “sanctification” of his life, he remains a sinner.

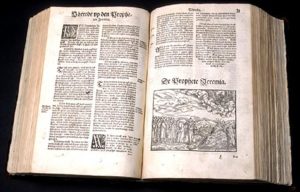

The authority of the Bible

Technical progress in book printing helped the Bible to be spread in a way that had previously been impossible. This new situation resulted in an altered relationship to the text. It was now studied with the « humanists’ » approach known to literary scholars of the Renaissance.

All Churches agreed on the supreme value of the Bible, but they differed in their ways of understanding it and of putting it into practice.

- In XVIth century Catholicism, the ecclesiastical authorities gave the exact meaning and interpretation of the Bible. As a result, the Bible could not be opposed to doctrines and practices of the Church, nor could it be interpreted in ways diverging from its teachings.

- For the Lutherans and the Reformed, it was not the Church that determined the meaning of the Bible, but it was the Bible that assessed the faithfulness of the Church. A rigorous study of the text with « humanistic » methods made it possible to grasp the exact teaching. Preachers and teachers must have solid university training ; their skills and competence were a necessary guarantee, even if the latter could not be perfect. The Spirit also sheds its light on Bible reading.

- The « Radicals » reproached the Lutherans and the Reformed with giving too important a role to « scientists » (« specialists »), and with replacing « papal tyranny by that of the linguists », as one of them put it. They advocated a spontaneous reading, popular in style, naive and inspired, since only the Holy Spirit can reveal the meaning of the Bible to the heart and mind of the believer.

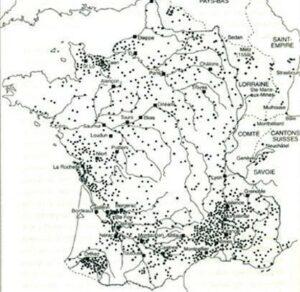

The Reformation in France in the 16th century

The kingdom of France remained predominantly catholic. However, the Reform Movement continued to develop in spite of religious persecution : the reformed Churches were set up from 1555 onwards. They were inspired by Calvin’s ideas, established a confession of faith and church discipline, so their communities were well organized on a local, provincial and national level.

The act of worship in the temple used Calvin’s liturgy, the central part of the service was the pastor’s sermon. Holy Communion was only celebrated four times a year, with both wine and bread being distributed. People also held services in their homes.

Protestants stood out from other believers in two different ways : both in their direct relationship to God, excluding the intermediary of saints or clergy and also in the way they led their private lives.