The churches

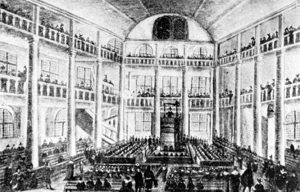

Once the wars and need to worship in secret were over, the Reformed communities started erecting buildings for worship, as allowed by the Edict of Nantes.

There were about 750 churches in 1620 but, following the terms of the Edict, they were seldom built within cities. They were buildings designed for preaching.

The largest one was in Charenton, built for the Paris community by Salomon de la Brosse. For the worshippers living in cities, going to church felt like going on an expedition.

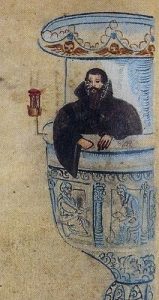

The sermon

It corresponded to what the Reformed Church today calls worship.

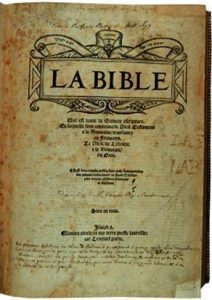

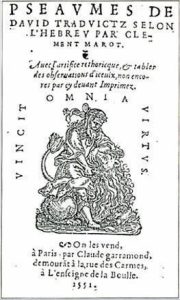

The pastors always preached on a text from the Geneva Bible (a version of Olivétan’s Bible, revised by pastors and professors in Geneva in 1558).

The general rule was, Sunday by Sunday, to follow a book of the Bible right to the end, and to explain it.

The sermon took place on Sunday mornings but also once or twice in the week, depending on the church community.

On fast days, there were three sermons in the church.

Fast days

Until the eighteenth century, the Reformers had a tradition of fast days, which has since died out. In the event of persecution, war, plague, famine, or other ills, a fast day was declared. There were :

- general fast days declared by the National Synod, compulsory for all churches on the same day ;

- Provincial fast days declared by the Provincial Synod ;

- specific fast days declared by the consistory of a church but nearby churches could join in.

On fast days, people ate little, shops were closed, any work was forbidden and people attended three successive services at church (reading of the Psalms and the Prophets were the most usual).

The sacraments : baptism and the Lord's Supper

For Protestants, only baptism and the Lord’s Supper are sacraments.

Children were baptised within days or weeks of their birth. It was the pastor who conducted the baptism, during public worship. The consistory was in charge of the baptism register that served as the civil register for the Reformers.

The Lord’s Supper, which commemorates Christ’s Last Supper, then his death and resurrection, was understood as spiritual food received as a sign of faith and a call to brotherly love. It was celebrated on a Sunday four times a year (at Christmas, Easter, Pentecost and in September or October). For practical reasons, the Lord’s Supper was celebrated again on the following Sunday so that the whole congregation had a chance to attend. Communion was given according to the social and church hierarchy : as a result, pastors took communion first, followed by the members of the consistory, the city officials in Protestant cities, the male members of the congregation and finally the female worshippers. The congregation would move forward, two by two, to encircle the communion table. After taking communion and receiving the blessing, they moved away and another group would proceed forward.

To take part in communion, the worshippers had to hand over a token which signified the holder was fit to attend the Lord’s Supper. Your right to attend the Lord’s Supper could be suspended for failing to observe the discipline of repentance. Tokens had to be collected from a local elder. From 1640, the token was also a way to check that the holder was a true member of the Reformed Church. Indeed, if a Catholic or a “relapsed Protestant” happened to take communion, it could serve as an excuse to close the church. The elders had to display extreme caution. If someone came from another parish, they needed a token from his or her own consistory.

Children were allowed to be present at the Lord’s Supper from the age of 12.

After the decision made by the 1631 National Synod in Charenton, Lutherans were allowed to participate in the Last Supper at Reformed Churches.

Other ceremonies

Marriage was not a sacrament, but the celebration of marriage took place in churches on a day of public worship. It had to be announced in church beforehand, on three consecutive Sundays.

The consistories held the marriage registers.

Recantation of the Roman Catholic faith was a ceremony of some pomp in the first half of the century. When Catholics converted to the Reformed Church they were not re-baptised. They usually renounced their Catholic faith publicly, in a Sunday service, after a long period of preparation and examination of their motivation and religious knowledge.

At the start of the second half of the century, it was sometimes prudent for the consistory to hear recantations rather than for it to be done publicly, and also for it happen in a parish far the person’s home.

In 1633, a royal edict forbade priests and clerics to convert. In 1680, another edict prevented all Catholics from converting. An edict in 1683 convicted pastors who were involved with converts.

Burials

From the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, the Reformed Church differed from the Catholic Church in so far as they had no public ceremony, at church or in the cemetery, for the dead. Reformed ideas tended to fight against superstitions and prayers for the deceased.

The Reformed thinking and Synods wanted simplicity at burials.

Royal decrees helped this by forbidding any convoy of over 30 people and any exhortation in public (February 1669).

Catechism

On Sunday afternoons, children and adults gathered together at church for catechism.

There were numerous catechism textbooks. The official book was that by Calvin dating back to 1542.

But by the middle of the century, the language used in this book sounded very outdated.

So, many other books were produced, the most famous of which is that by Charles Drelincourt (1642). These did not pretend to replace Calvin’s, but were intended to be read by the congregation.

After each Lord’s Supper service, there were “super catechism” sessions to sum up doctrinal teaching. You could only participate in the Lord’s Supper if you understood the doctrine, since communion was, in a sense, a confession of faith.

Private or family religious practice

Morning and evening worship within the family circle was commonplace among members of the Reformed Church. Parents, children and servants all attended, and it was presided over by the head of the family (sometimes, in noble households, by the local pastor). A short prayer was said, one or several chapters of the Bible were read and a Psalm sung. In addition, grace was said before a meal and after it, they gave thanks.