The origin of Revivals

The protestant community called « Revivals » such movements as attempted to « revive » a faith that had become dull, somnolent and repetitive. Revivals wanted to promote a more existential and more sentimental piety, committed and demonstrative, based on personal experience rather than on the adherence to specific teachings. They protest against a religion of a predominantly intellectual nature. Akin to the Romantic Movement, they give emphasis to feeling, and are therefore very close to the German theologian Schleiermacher, one of the founders of liberalism.

They were inspired by English Methodism and Lutheran pietism and were characterised by :

- The call to conversion. Conversion did not mean « a change of religion », but « the change from a conventional faith to an active faith ». Conversion was considered as being a “new birth”, with a radical change in one’s existence resulting from a spiritual and existential experience at a given date and place. God himself acts in the conversion of the heart.

- Exaltation played an important role. It was upheld by singing and by the kind of preaching that instils doubt and moves the congregation. A few hysterical reactions during Revival campaigns provoked mistrust and scorn.

- Heavy insistence on the Bible. Study groups were organised to increase Bible knowledge. Such Bible study was more of an existential nature than historical or philological. The Revival Movements were very active in publishing the Bible through the Bible Societies.

- Revival movements took up traditional themes such as the salvation of sinners through Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, insisting on the experience of sin and rebirth. They were inspired by the Swiss theologian Alexandre Vinet, one of the leading thinkers of the revival and liberal movements.

- The importance of evangelisation. Every converted Christian should contribute to spreading the Gospel and faith by word and book. Revues and short tracts were distributed by “hawkers”. Revival Movements were responsible for the founding of many charities and overseas missions, notably in Africa and the Pacific islands.

- Revival Movements were at the forefront of social progress and were very active in education, health care and helping the poor. Women played an important role and had access to practically the same responsibilities as men.

Implantation in France

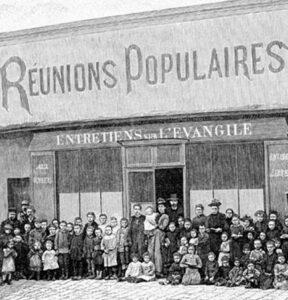

Swiss, and especially British preachers travelled all over France spreading the Revival Movement. Ami Bost and Charles Cook were the best-known, and introduced Anglo-Saxon customs, such as small group meetings rather than large assemblies, hymn singing with romantic words and music, whereas the reformed would traditionally sing psalms only.

In Paris the Revival Movement influenced the upper middle-class and penetrated aristocratic drawing rooms, such as Madame de Staël’s who was very active against slavery, and later in her daughter’s, the duchess de Bröglie. A cosmopolitan and elegant congregation met regularly in the independent Chapelle Taitbout ; its financial support was to be decisive for protestant charities.

The Revival Movement also reached the provinces and rural areas. In the Alps Felix Neff was active in evangelization as well as education and economic development. The success of his work was widespread.

On one hand revivalists created communities often separated from reformed parishes and independent from the State. On the other hand they infiltrated Concordat-bound parishes in which they were present and active in a more discreet way. 19th century Church organisation gave each parish a lot of independence. Orthodox and liberals wanted Church and State to be linked, claiming that this would prevent small groups from taking over parishes and annexing them. Revival partisans favoured the separation of Church and State which, they said, would give them more facilities to develop their influence.