The adversary of Lamennais

Samuel Vincent was born in 1787. The very year when, by the Edict of Toleration, King Louis XVI gave back to the Protestants, if not their prerogatives, at least the right to lead a normal life in France. He was a typically representative example of a new generation of ministers who grew up during the Revolution, the Directory and the Empire and set the tone for Protestantism in France during the Restoration and the July Monarchy. After studying in Geneva, his whole ministry was spent in Nîmes ; he may be considered as a no less typical representative example of the southern , non-Parisian circles of French Protestantism in the early 19th century .

Called upon to preach during a religious service celebrating the return of the Bourbons to the throne of France on 5 June 1814, he stressed the difference between Protestantism and Roman Catholicism, he asserted that « variety in opinions and ideas, provided it is accompanied by charity, far from being harmful to religion is in fact beneficial to it. It encourages research, promotes enlightenment, gradually dispels error, purifies religion and ensures the victory of truth » (“la variété d’opinions et d’idées, dès qu’elle est accompagnée de charité, loin d’être mal pour la religion, est un véritable bien. Elle encourage les recherches, favorise les progrès des lumières, dissipe peu à peu les erreurs, épure la religion et fait triompher la vérité »).

The evolution of the political situation soon pushed him to the forefront to defend his point of view. In his famous Essai sur l’indifférence en matière de religion (Essay on the indifference to religious matters) published in 1817, Father Félicité de La Mennais (or Lamennais) defends « the need for unity as far as faith is concerned, and for a permanent and decisive authority to maintain it » (“la nécessité de l’unité en matière de foi, et d’une autorité permanente et decisive pour la maintenir”) along with harsh criticisms against Protestantism which he accused of being, since its origin, the source of all rebellion. Vincent was the only Protestant to respond to Lamennais in 1820 with a first 223-page book entitled Observations sur l’unité religieuse, en réponse au livre de M. de La Mennais (Remarks on religious unity as an answer to the book by M. de La Mennais). Then followed, the same year, Observations sur la voie d’autorité appliquée à la religion (Remarks on authority as applied to religion), an answer to a second , more direct attack from Lamennais. In it, Vincent took up and developed the idea already suggested in his sermon of 1814, but with a strength and a broadmindedness that revealed him as a thinker to be reckoned with.

The theologian

Vincent had already played his part in the revival of French Protestant thought by publishing the translation of two English books : in 1817 La Philosophie morale by William Paley (The Principles of moral and political Philosophy) and in 1819 , Des preuves et de l’autorité de la révélation chrétienne by Thomas Chalmers.(On the proof and authority of Revelation). In 1820 he took an additional step, decisive for French Protestantism of his time, by beginning the publication of an important theological review entitled Mélanges de religion, de morale et de critique sacrée ( Mixtures of religion,moral and sacred criticism ), 10 volumes of which are published between 1820 and 1825. As well as publishing numerous original pieces, he was one of the first to make the theological options of Schleiermacher known and to show the importance of Kant in Protestant ethics and theology. The publication of Mélanges was suspended due to the circumstances, but in 1830-1831 he published four volumes of another periodical, Religion et Christianisme (Religion and Christianity).

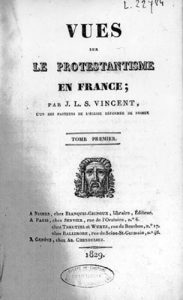

In the meantime, in 1829 he published his most important work, the richest in theological openings upon the new century : Vues sur le protestantisme en France (2 vols.) (Views on Protestantism in France, 2 volumes.).

« The content of Protestantism is the Gospel, its form is freedom of examination » (Le fond du protestantisme, c’est l’Evangile ; sa forme, c’est la liberté d’examen). This often quoted sentence gives an inkling of the general tone of the book. In it, Vincent stresses the difference between religion, the living faith of believers, and ecclesiastical organisation. He recalls that the Church is not essential to salvation, it must merely be useful and efficient, which is only possible if it acknowledges each person’s full freedom of examination, especially in matters of faith.Vincent also stressed the distance between the Bible and Revelation as such, which is primarily a matter of conscience, even of individual conscience. For him the Reformation cannot be limited to what the reformers said or wrote : the latter could not immediately display all its potential.

For Vincent, spiritual freedom and freedom of examination go together. He was therefore one of the great instigators of the liberal trend in French-speaking Protestantism. His vision of man was rather optimistic (this was implied in his concept of freedom and he did not mention “original” sin) ; he claimed that freedom of examination be applied to the biblical texts and wanted them examined scientifically, in accordance with the historical methods of his time.

At the same time, Vincent cared for the growth of believers’ individual piety, while warning his fellow Protestants against ready-made concepts of faith. Faith requires permanent and individual efforts in such areas as thought and freedom. This brought him close to the Revival Movement. In fact, he advised his fellow ministers to show in their ministry the same zeal and the same spirit of consecration as were shown by representatives of the Revival Movement, but without adopting their doctrinal and spiritual narrowness. Vincent’s defence of the synodal system within the Reformed Churches is noteworthy ; it led him to criticize the obstacles put in the way of the inside workings of these Churches by the Organic Articles of 1802 ; but he never attempted to break the links with the State.