Asserting Protestant identity

It was with Napoleon’s Concordat that he Protestant Churches were once more recognized in France. A consistorial organization was imposed upon them but, though quite familiar to the Lutherans, was not well adapted to such Reformed traditions as had survived in exile. Nor was this form of organization adapted to the idea the Protestant Church had of its own mission. The Protestant Church did not wish to take initiatives that might be too tightly controlled by the State.

It was with the support of the Protestant Churches in Geneva, England, and Germany the Protestant Church regained its own proper identity alongside both the Catholic Church and the State. These Churches provided the means and the tools necessary for a theological and dogmatic “Revival”. From there on, the French Protestant church began to exercise its freedom of action in various practical fields.

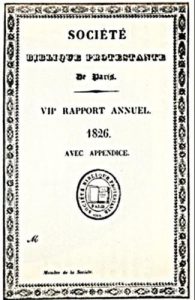

There were soon to be an increasing number of statesmen amongst the Protestants, and these aimed at applying the essential principles of Protestant education. However the Church’s role could not be defined by the State. This is why Protestants strove to create all sorts of societies throughout the nineteenth century, most of which were recognized as non-profit-making and remained free to define their activity. No fewer than 236 service organisations of local or general interest were set up, ranging from the first Bible Society (1811) whose aim was to provide congregations with sufficient Bibles, to the Pastoral Cycling Association (1891) responsible for evangelising remote areas. Likewise the John Bost Hostels, and an institution for the deaf, old peoples’ homes and associations to bring relief to pastors’ widows, etc. All these service organisations were meant to give the image of a free and multi-denominational Protestantism in a not so open society. As a matter of fact, the July Monarchy era was more favourable to such activities than the second Napoleonic Empire. It was under the Third Republic that things became far easier.

Many service organisations started in the nineteenth century kept growing and developed throughout the twentieth century. Efforts were constantly made to modernize them and thus keep up with the needs of current times.

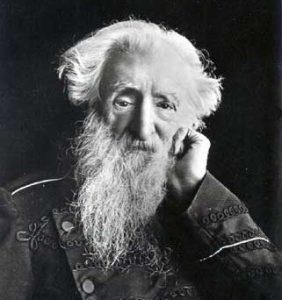

The practice of the Christian faith was honoured by these service organisations founded by Protestants whose names are still remembered today (Monod, Mallet, Vermeil, Hottenguer, Schlumberger, Boissonnas, Bœgner, Bost, etc., families of pastors but likewise of bankers, scholars, and industrialists).

The Protestant definition of "service"

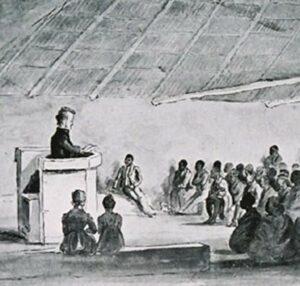

“We – and perhaps more so than others – are well aware of the value inherent to the very principles of freely consented associations. Such associations are capable of uniting the different forces necessary for the vocational training so useful to charity organisations or to any other sort of work. We resort to all human means that advocate caution and common sense. But we must acknowledge that without the Gospel we would remain helpless when faced with evil, whatever be its form. Without the Gospel, what comfort is there for the sick, what peace for the distressed, what consideration for the poor, what light for those with a troubled conscience, what lifting help to those who have fallen, what example for the children we must steer through life, what renewal for the elderly who feel their strength dwindle and life slip away ? The results we are seeking may not always be fully appreciated in this world”.

(Dictionnaire des Oeuvres protestantes, p. 184, note by S.Monod)

The different kinds of service organisations

Besides the major service organisations, (such as missions or pastoral, charity and educational services), others were more specifically linked either to the Revival Movement or to liberal theological trends. Many were ecumenically orientated, and as such, open to the various Protestant denominations.