Concern for the pastoral staff

Protestant Faculty of Theology Paris © SHPF

Protestant Faculty of Theology Paris © SHPF

Even though French Protestants recovered their public identity in the nineteenth century, they were still poor in means after their long ordeal. The issue of places of worship inevitably came up and many church buildings were erected. But the most important issue was the training of a sufficient number of pastors and the guarantee of their living conditions. This accounted for the creation of a certain number of pastoral services.

One of the first tasks to undertake was that of facilitating the recruitment of pastors. Some services aimed at creating free theological faculties alongside the State Faculties of Theology (e.g. the Montauban School before it became a State Faculty). Preparatory Schools with more modest academic aims were likewise founded for short term training focusing on the most immediate needs. Amongst these featured the Glay Institute founded in 1821 and the Batignolles School first founded in Lille in 1846 and then moved to Paris in 1847.

Some organisations aimed at creating stronger links between pastors sent to isolated parishes (The Regional Pastoral Unions in the Cèvennes, Ardèche, Normandy) or who adhered to a specific theological trend (The Liberal Pastors’Association founded in 1885).

Others focused on providing the pastors with further education. (Various theological societies were created as progress was made in Biblical exegesis or when the Roman Catholicism went through its modernist crisis).

At the beginning of the Third Republic, an Association for the Encouragement to study at the Paris Theological Faculty was created. It provided scholarships and travelling facilities for students.

Lastly, many aid services dealt with living conditions of pastors and their families and tried to meet with matters of contingency.

The Pastors' Contingency Service

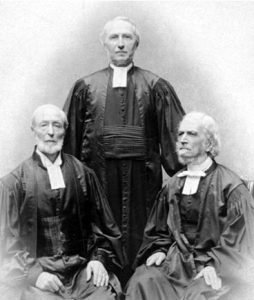

Triumvirate of pastors in the 19th century © S.H.P.F.

Triumvirate of pastors in the 19th century © S.H.P.F.

Under Concordat rule, pastors were paid by the State and could even get pension benefits. However, such public funding was low since the status of pastors was assimilated to that of Catholic priests. The fact that they were heads of families or that few parsonages could be provided was not taken into account. Pastors allowances had to be supplemented and pastors had to be provided with housing in case of urgent need (e.g. the Service Organisation for the Poitou parsonages).

Besides, since Concordat conditions were not always accepted, many free churches were established and these existed without State control. Such a situation had to be concretely followed up.

One of the most serious issues concerned pastors’ pensions. State allowances were so low that many worked beyond a reasonable age.

As a result, various associations had been created in order to improve the situation. They gathered and managed their own funds made up mostly of donations and bequests. In fact, it was only as from the Second Napoleonic Empire that issues related to mutual help within a more and more recognized community could be dealt with in a concrete way, and this with the help of bankers and high ranking Protestant administrative personnel. A certain number of pension funds were created for the pastors of the Reformed and Lutheran Churches. Pastors’ widows were likewise looked after, but at local or regional levels and not so much at a national level (Association of Protestant Widows, etc.).

These complementary funds were created in 1863 under the initiative of Mr. Dassier, Chairman of the Executive Board of the PLM Railways. Besides offering the guarantee of an important leg, he took the most useful administrative steps and set up a reliable board of directors (the Vernes, Mallet, Hottinger families were involved). He had the legal statutes of the funds approved by the “Conseil d’Etat” and made sure that the state-owned bank, the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations, would provide the banking monitoring of the assets.