Peaceful times

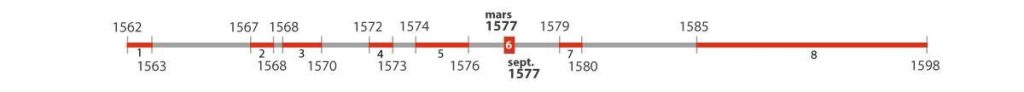

As soon as the Edict of Beaulieu was signed, it was difficult to implement as it prompted opposition. The King’s legitimacy was questioned because he had yielded too much to the Protestants. The Princes’ greediness, the huge amounts given as compensation, especially to Duke François d’Alençon and Jean Casimir, drained the Treasury and increased the tax burden, outraged the common people. The people’s precariousness and poverty were siezed upon by the clergy. The infuriated Catholics created defensive leagues.

The General Estates summoned in Blois in November 1576 were held in a very unfavourable climate towards the Huguenots, as most of the representatives were Catholics. Returning to a single religion was requested. Despite the opposition of some who considered that the King should not take sides for one religion, the State being above religions, most registers of grievances demanded Protestant worship to be banned, pastors to be expelled, Catholic worshipping to be attended. The Edict of Beaulieu was abolished.

For the Guise party, the monarchy had failed to fight heresy, and a League of lords and cities had to be created to reestablish peace. The initiative was taken by Jacques d’Humières, Governor of Picardie, who had lost the province after the Peace of Beaulieu to the benefit of Henri de Condé – it was the first league called « de Péronne”. The aim was to restore the previous monarchy and the privileges of the Church of France. Going back to the past was demanded, and the idea of reforming the clergy rejected. The Catholics were enjoined to rally to the League. Members pledged fidelity to one another. Henri III was threatened and took the lead of the League, and declared to the council that he would accept only one religion in his kingdom.

Times of War

As soon as the Edict of Beaulieu was abolished, conflicts started again, especially in Dauphiné and Provence. The Catholic party seemed able to win. Duke Fançois d’Anjou, back at the Court and head of the Royal army, won back La Charité-sur-Loire, a strategic place to cross the Loire river, and was headed towards Auvergne. The siege of Issoire, a Protestant stonghold town, was started on the 20th of May. When it fell there were extremely violent scenes as a great number of inhabitants were butchered.

In the Languedoc, Henri de Montmorency-Damville, who had rallied the king, was opposed to François de Coligny, the Admiral’s son, and tried to reconquer Montpellier when news of a peace agreement was known.

Due to the lack of financial help, as the representatives denied the King any financial means, negotiation was urged. General fatigue could be felt, and a compromise was reached, the Peace of Bergerac in September 1573. It restricted the previous concessions of 1576, but was not as severe as the Edict of Boulogne in 1573. It restricted worship to suburbs of towns by bailiwick, even in towns with a majority of Protestants, and reduced mixed courts of law.

The Protestants kept their eight stronghold towns, but for six years only. As for the leagues, they were disbanded because Henri III not only feared the Duke of Guise, but a lot of people claimed that the sovereign could not be head of a league without questioning the principle of royal authority which should be above the parties. Once gain these agreements satisfied neither party and could be nothing but truces.