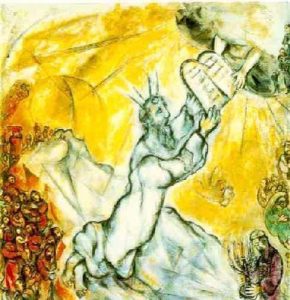

An endless source of inspiration for artists

Both the Old and the New Testament provide an endless supply of stories which have always inspired artists ; they are about men and women who have colourful adventures against a background of arid deserts or noble cities. Little by little certain themes became particularly popular : Adam and Eve, Noah’s ark, the ten plagues of Egypt, David and Goliath, Judith and Holofernes, the miracle of the draught of fishes, Jesus’ meeting with the Samaritan woman, Mary and Martha, the raising of Lazarus, doubting Thomas and the risen Christ, the men on the Emmaus road. After the Council of Nicaea II (787AD), which had restored the worship of icons, these narratives were often used to inspire pictures. Of course God himself was never depicted, as this was forbidden by the Law. Artists used various symbols to portray the divine presence – for example, in the synagogue of Doura Europos (about 256AD), it was depicted by a hand emerging from a cloud : both Michelangelo and Chagall used the same symbol. Some subjects were treated in a way that became progressively less and less Biblical. An example of this is the subject of Paul falling off his horse on the way to Damascus (Acts 9, 4 ; 22, 7 ; 23, 13 ;). This was illustrated by Bruegel the Elder (1525-1569) and later by Caravaggio (1571-1610). The story had caught popular imagination to such an extent that even exegetes were sometimes surprised to discover that there was no mention of this in the Bible. Some painters depicted a certain interpretation of the Bible in their works and thus portrayed their own theology as part of their art. For example, Maurice Denis painted a picture of Pentecost (in the Saint Esprit, a Catholic church in Paris), in which Mary was placed at the centre of the composition, whereas Emil Nolde, who was closer to the text, only depicted the huddled group of disciples. Works of art inspired by the Scriptures call for a certain interpretation of the text, a kind of pictorial theology. Although contemporary art is no longer under the influence of the Bible, artists continue to use Biblical themes. Some aetheist, artists do so in order to confront major cultural issues, but with no religious aim. Pablo Picasso worked on the theme of the crucifixion quite often and so did Francis Bacon. Other artists who were believers, such as Kandinsky, Jawlensky, Manessier, Rouault or Arcabas were inspired by the Scriptures, enriching their faith and their art.

The Bible and Literature

Apart from the mystery plays in the Middle Ages, there are many other examples of the Bible in literature, especially during the Romantic Period : Victor Hugo, Les Contemplations (1856), La Légende des Siècles (1859-1883), or Chateaubriand, Le Génie du Christianisme (1802). but we cannot exclude modern literature : Thomas Mann, Joseph and his brothers (1933-1943), Michel Tournier in Eléazar, La Source et le Buisson(1998), Sylvie Germain used the apocryphal book of Tobias as a source of inspiration for Tobie des marais (1998). In 1998 Gérard Theissen, a well-known exegete, used his imagination to write L’Ombre du galiléen (1988).

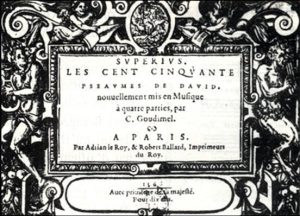

The Bible and Music

Music also has been constantly inspired by the Bible : hymns, Gregorian chants, the psalms set to music by Gaudimel (around 1560), and J.S. Bach’s Cantatas, Passion according to Saint John, 1724 and then the Passion according to Saint Matthew, 1729. Several works take their inspiration from The Seven Last Words of Jesus on the Cross. This is a compilation of 7 short phrases spoken by Jesus, taken from all the Gospels, which inspired Joseph Haydn in the 18th century, Charles Gounod and César Franck in the 19th century and C. Looten in the 20th century. Olivier Massiaen’s work, Les Visions de l’Amen (1943), is like a song in praise of the creation.

The Bible and Cinema

Cinema producers have explored Biblical symbols, myths and epic tales. Some films recount the life of Moses (The Ten Commandments), the disciples (Pablo Pasolini’s The Gospel according to St. Matthew), or Jesus (Fellini, Scorcese, P.Arcand), while others relate stories based on important Biblical topics : sinfulness and grace, fortitude in weakness, strength and redemption. For example, Fellini’s La Strada (1954), Spielberg’s E.T. (1982), G. Axel’s Babette’s feast (1987) or Wachowsky’s Matrix (1999).

The Bible in everyday language and advertisements

In this secular day and age, our culture remains steeped in Biblical references, whether we realise it or not.

We are all personally affected by this : by chance we may use a word or a symbol which comes straight from the Bible. Some expressions are more literary : wielding the knife (Gen 22,1-19),or poor as Job (Job), others historical : as old as Methuselah (Gen5,27), the mark of Cain (Gen 4,15) ; while some expressions have become so much part of everyday language that their Biblical origin has been forgotten : for a pittance (Pro 28,19), let the reader understand (Mat 19,12), or as white as snow (Ps 51,9).

Advertising exploits these cultural resources even if they are distorted or parodied. We often see Adam and Eve, Moses, God, the Garden of Paradise, the Ten Commandments or the Last Supper being used to promote commercial products. Bible verses are even quoted but in a deformed or incomplete way : “Peace on earth”, “Render to Caesar”, “Blessed”. These distortions sometimes incite anger : the Last Supper being used to sell the latest Volkswagen Golf or the clothes made by Mathé and François Girbaud have been banned following lawsuits.

Caricatures have long been inspired by things Biblical. At the time of the Reformation, wood engravings were handed out with the aim of discrediting one or the other religion : they played on the opposition between vice and virtue depicted as two churches in the Lord’s vinyard (Erhard Schön) or that of the law and grace (Lucas Cranach). Nowadays this tradition is maintained by Plantu, in his own inimitable style : in the newspaper Le Monde, he often takes examples from the Bible to wittily denounce problematic situations.

Jean Eiffel published the mediaeval Biblia paupera and in 1953 he created a cartoon called The Creation of the World while David Ratte, began his trilogy Voyage des pères, with Alpheus and Jonah and finished with the figure of Simon