The Declaration of 1724

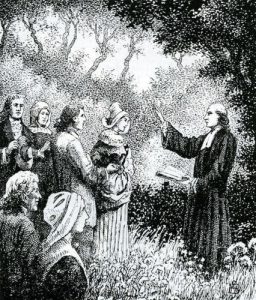

The Regent died in 1723. On coming to power, Louis XV revived all the anti-Protestant law of Louis XIV, in the Declaration of 1724. This declaration caused consternation among Protestants, who even thought of rebelling. Antoine Court travelled the regions to preach calm and to call a synod in order to get across his point of view.

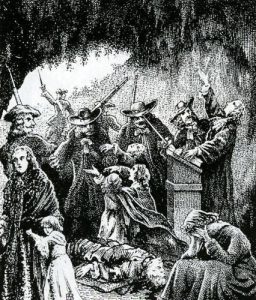

In fact, the 1724 Declaration was not really followed until 1726 when Fleury, Bishop of Fréjus, became Prime Minister. Fresh arrests and convictions were made. In 1730 soldiers took Bibles, Psalters and other religious books from the Protestants of Nimes, and they were burned in the public square.

In 1732 the pastor Pierre Durand was arrested and sentenced to hang. But the persecution did not stop the growth of the Church or young pastors taking over the helm. Languedoc sent preachers, then pastors, to the provinces of Guyenne, Rouergue and Poitou.

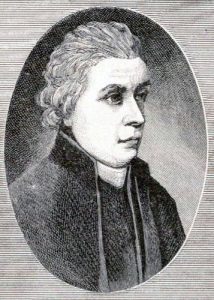

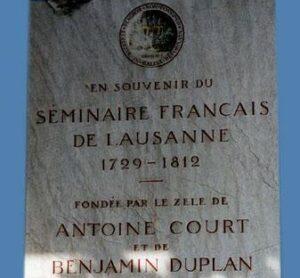

In 1729, danger forced Antoine Court to leave France for Geneva, where he had already sent his wife and children. In the end he went to Lausanne where he oversaw the training of future pastors for the “Church of the Desert” at the Lausanne Seminary. He supported the French Church through many letters. He relentlessly defended practices of “Church of the Desert” meetings, always frowned upon among the Refuge, and sought help for persecuted churches. He undertook to write the history of the Reformed Church since the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, but only published the part about the War of the Camisards. He assembled much documentation that is now in Geneva : papers of Court (that have still not been made full use of).

The truce of 1744

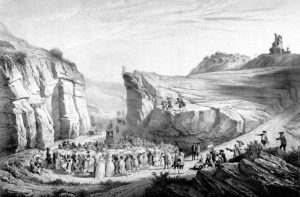

In 1743 Fleury died, France was at war (the War of Austrian Succession, 1740-1748) and the soldiers were busy elsewhere. There was less persecution. In Languedoc, Protestants met in the open and the new governor, the Duke of Richelieu, turned a blind eye. Protestants believed that tolerance had finally arrived. The bourgeoisie and nobles that had condemned “Church of the Desert” meetings began to attend them, baptise their children and get married there.

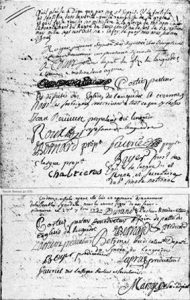

At the national synod of 1744, in Lédignan (Gard) ; Antoine Court was present. It was decided, in order to pacify the Catholic clergy and win over the Court to the Protestant cause, to ban pastors from preaching about, or stirring up, controversy with Catholics. A draft letter, calling for freedom of conscience, was written to the king and Duke of Richelieu.

Antoine Court was appointed Deputy General for Protestant countries, replacing Benjamin Duplan who had been appointed by the 1727 synod. The job of Deputy General was to solicit funds from “Refuge” countries to help the French Church and provide for students at the Lausanne Seminary.

Resumption of persecution

From 1745 persecution resumed. The Assembly of Catholic Clergy called for new measures against worshipping in secret. The new Intendant of Languedoc, Le Nain, applied policies more forcefully than his predecessor. In Dauphiné two pastors were executed : the young Louis Ranc and 80 year old Jacques Roger, after more than 30 years in the “underground” ministry. In Vivarais a young pastor was executed and another in Saintonge.

In 1746 the persecution was relaxed. A France at war feared an alliance between the Protestants and foreign powers, but the Protestants remained loyal to the king. After the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748), persecution resumed : children were kidnapped, towns holding banned meetings were heavily fined and soldiers were stationed in defiant towns.

From 1750, the new Intendant, Saint-Priest, began enforcing Catholic re-baptism of children baptised in the “Church of the Desert”. The refusal of parents caused horrific scenes. Some Protestants left their homes and hid in the woods. The Court feared fresh insurrection and things were relaxed at the end of 1752. The Duke of Richelieu returned to Languedoc :

From Lausanne, Antoine Court called on French Protestants to continue with “Church of the Desert” meetings, but for them to be smaller and held at night once more. He published a dissertation called The French Impartial Patriot (Le patriote français et impartial) (1753). With reference to history, he showed that French Protestants had always been loyal to the king, that “Church of the Desert” meetings were not rebellious, that French Protestants were honest people who only wanted to have freedom of conscience.

The final persecutions

By the end of 1752 “Church of the Desert” meetings, as well as marriages and baptisms, had begun again. Hope returned : But in 1754, 30 battalions went to Languedoc and stopped all meetings. They tracked down the preachers and their wives. Paul Rabat’s wife hid in the woods for two years. They even offered passports to pastors so they could leave the country, but most remained.

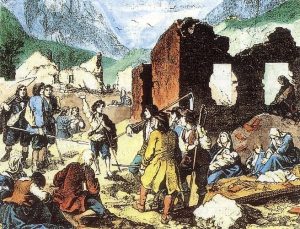

In 1756, the Duke of Richelieu was replaced by the more tolerant Duke of Mirepoix. He allowed meetings so long as they were held discretely. He even corresponded with moderate pastors like Paul Rabaut. Encouraged by pastor Louis Gibert, the Protestants of Saintonge had established Houses of Prayer since 1756. Following them, the Languedoc Protestants thought about rebuilding the churches, but the military immediately demolished everything.

Meanwhile persecution continued in Agenais and at Orthez, in Guyenne, Béarn and Dauphiné This did not mean that persecution was widespread but rather that there were sporadic” warning shots”.

Even though there was a final execution – of pastor François Rochette at Toulouse in 1762 – historians agree that the new period of tolerance towards Protestants began in 1760. There were, in 1760, more than 50 pastors working in France. The Court could not hope to convert the Protestants. 1760 also saw the death of Antoine Court, who oversaw the secret reconstruction of churches during the Heroic Period. He died in Lausanne on 15th June after a long illness.