An act of sovereignty

In spite of many difficulties, King Henri IV finally managed to impose this act of sovereignty. This element made it differ from previous edicts, although basically they shared many of the same ideas ; but the latter had constantly been called into question. Its immediate aim was to obtain peace, but its declared long term objective was to procure religious harmony throughout the kingdom. In the introduction, the king stated his wished that “a good peace” (“l’établissment d’une bonne paix) would enable those of “his subjects who adhered to the supposedly reformed faith » (“sujets de la religion prétendue réformée”) to return to « the true religion » (“la vraie religion”), his own, « the catholic apostolic and roman religion » (“la religion catholique, apostolique et romaine”).

The elaboration of the edict had been no easy task and had required a great deal of negotiating. Both Catholics and Protestants needed reassuring and all had to regain their confidence. The result was a compromise. The edict established civil equality between Catholics and Protestants as well as the conditions necessary for the peaceful coexistence of the two ; however, the edict set limits to protestant worship.

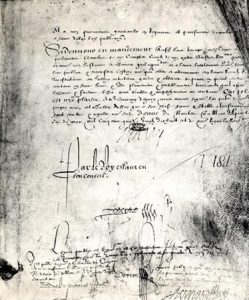

Documents of the edict : four distinct texts

- A first warrant guaranteed the Protestants an annual grant of 4500 crowns ; this enabled them to hold their services and especially to pay their « ministers » (pastors).

- The actual edict itself consisting of 92 articles, was “permanent and irrevocable” – meaning that it could not be revoked by a new edict.

- A second warrant guaranteed the Protestants 150 places of refuge for a period of 8 years – 51 of these were strongholds, which the Protestants were to garrison for their security. (This warrant was renewed in 1606 and 1611 but suppressed by the « Peace of Alès » in 1629).

- 56 articles, said to be « secret and specific », but oflesser importance and dealing with local situations.

The clauses of the Edict of Nantes

Some articles favoured the Roman Catholic Church:

- in most towns, only catholic services were allowed ;

- all buildings originally belonging to the Catholics were given back to them ;

- mass had to be celebrated throughout the kingdom, including the Béarn country ;

- according to the usual practice, Protestants had to pay tithes to the Catholic parish priests.

Other articles favoured Protestants:

- freedom of opinion was granted ;

- protestants were allowed to organize their synods ;

- in matters of education, Protestants and Catholics had equal rights ;

- absolutely assurance of access to positions of important public responsibility ;

- Protestants were allowed freedom of worship in certain specified places only – elsewhere, it was strictly forbidden, notably at the court, in Paris and within an area of five leagues around the capital, as well as in the armed forces.

The edict likewise made mention of some general provisions :

- a general amnesty for all crimes committed excepting those of a particularly atrocious nature ;

- all provocation, revolts and the stirring up of the people was forbidden ;

- all men stood equal before the law ;

- everyone had the freedom to abjure, that is to change their religion ;

- legal impartiality was guaranteed by law courts made up of Catholic and Protestant legal officers ;

- emigrants and their children were allowed to return.

Registration of the edict

The edict had to be registered by all parliaments, some of whom were openly hostile to such a decree. Henri IV had to impose it on the parliament in Paris, and in Rouen the parliament took eleven years to ratify it.

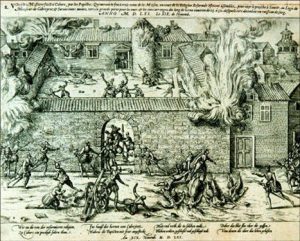

Events from the signing of the edict to its revocation

Throughout his reign, Henri IV made sure that the edict of Nantes was properly enforced. He even allowed Parisian Protestants to gather for worship in Charenton, less than five leagues away from the capital.

But under Louis XIII the Protestants lost their strongholds, and depended entirely on the king’s good favour.

The beginning of Louis XIV’s reign (from 1643 to 1660) was a time of religious peace, but from 1660 onwards, when Louis XIV took all power into his own hands, the edict was applied in a restricted manner. In 1680, persecutions began once more. The king’s dragoons inflicted terror as they sought to enforce conversions ; this period is referred as that of the « dragonnades ». In 1685, the King – convinced that most Protestants had by then become Catholics – signed the revocation of the edict of Nantes in Fontainebleau.