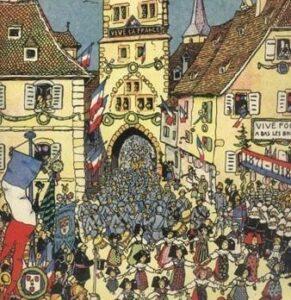

The « sacred union »

Germany’s declaration of war on France on 2 August 1914 caused intense anguish, but determination and a sense of duty won out, abolishing the differences between the partisans of rigour and pacifists. The political and religious conflicts which had so often torn the country apart were forgotten, and the feeling of legitimate defence, even a desire for revenge against German aggression was almost unanimous. Protestants and Catholics, be they soldiers or chaplains, came closer to each other. All the « spiritual families of France » were united. The insinuation that the conflict opposed Luther’s protestant Germany to Joan of Arc’s catholic France was rejected by the majority. The protestant, Gaston Doumergue, was a prominent member of Viviani’s government. The strong belief in final victory was shared by all.

The churches during the war

The responsibility of Germany and Austria, who had contravened international treaties, was recognised and the war considered just and legitimate by the fatherland of human rights. The Protestants were disgusted by the attitude of most prominent German Protestants who put God and Christ at the service of their Kaiser’s ambition. Benedict XV’s appeal to peace was considered by most French people as favourable to the Central Powers.

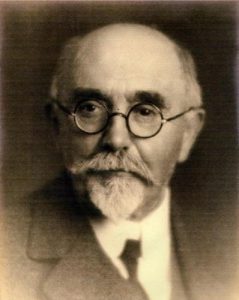

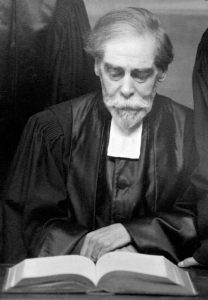

Few protestant preachers called forth the Lord of hosts and proclaimed, as the Rev. H. Monnier did, that “the cause of France is sacred in itself…and is indistinguishable from the cause of God’s reign.” The great majority demonstrated neither idealisation nor exaltation of the war.

On the other hand, the deterioration of the political climate in 1917 – murderous attacks, the gap between the men at the front and the “profiteers” at the rear – threatened national unity, so that pastors of Calvinist tradition reminded citizens of their duties towards the state, and of « the loyal will to fight until the final Victory, the Holy Victory » as G. Boissonas said. In February 1917 the Manifesto published by the French Protestant Federation rejected the idea of a negotiated peace, that « peace without victory » advocated by the president of the United States, Woodrow Wilson.

What vision of Christianity ?

The slaughter of French Reformed, the « evil outbreak of homicidal fury » as W. Monod defined it, led to liberals questioning their optimism and led many an “evangelical” to wonder about divine omnipotence. Like the Catholics, some asked themselves whether the war was God’s judgement, « The heavenly Father’s just chastisement of human sin » as the Rev. J. Pfender said.

When nations which called themselves Christian fought so ferociously against one another, many pessimists wondered whether the war was not caused by a « nationalist » Christianity, which had violated the universal and pacific dimension of Christ’s teaching.

The call for church renewal

The Versailles treaty of 28 June 1919 was partly based on President Wilson’s famous « fourteen points » (January 1918) which opened up the possibility of a new international order which would be implemented by the League of Nations, created in 1923. The « generation of fire » deemed change and the opening up of the churches indispensable. Division between Christians was a scandal. In July 1919 the national synod of the Union of Reformed Churches voted a resolution to organise a general assembly of all the Reformed to decide on a true union of the churches. Youth movements, the FFCSA (French Federation of Christian Students’ Associations) along with radical lay people, strived to bring together the various streams of Protestantism. The European cataclysm had shaken believers out of their spiritual apathy and made them aware of the need for Christian unity.