Within thirty years, David Haviland managed to pass on to his descendants a first rate industrial product which had a significant part of the market in the States.

The Havilands belong to an old family which settled in the Cotentin area; they originally came to France at the time of the Norman invasions and they still have a branch in England today. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, William Haviland emigrated to America – he was in Providence in 1648, where he joined the Quaker colony. After six generations of living in the American Colonies, David Haviland, born in 1814, ran a shop with his brother at No. 47 John Street (near Wall Street) in New York; they sold various articles, including china from England. This little business would later become the Haviland Brothers china company in 1852 – by this time other members of the family would also have joined the firm.

Towards the end of the 1830’s, the economic situation in America was catastrophic and this is probably why he tried to bring more variety to the range of products he had on sale. He achieved his aim by importing a new kind of “hard paste” china which until then was little known in the States. This necessitated his emigration to France with his wife and child. In the autumn of 1841, he reached Foecy where he stayed with fellow Quakers like himself who were china makers. Indeed the general approach of the Haviland family was quite different to that of other local protestants and this was most probably due to the fact that they belonged to this particular denomination. He travelled to Limoges, where he arrived in April/May 1842, together with his wife Mary and their two-year old son Charles. A second son, Theodore, was born in August of the same year. They chose Limoges because kaolin had been found nearby – this is a very pure white clay used to make china.

A thriving industrial business

When David Haviland arrived in the Limousin area he could not speak French and knew nothing about the techniques of making china. However he went round several factories and chose some particular articles of china which he sent back to the States to be sold in his brother’s shop. They were so popular with the customers that he was able to buy his own equipment in order to make the kind of china which would suit American taste.

Encouraged by his success, David decided not only to continue making china himself but also to have this “plain” chin decorated, in accordance with his own ideas.

Due to David’s efforts, exports of French porcelain to the States increased enormously, from 753 to 8594 parcels between 1842 and 1853. The Haviland Company took part in the World Fair in New York in 1853 and won a medal.

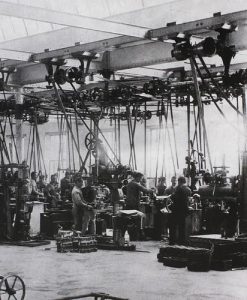

Now that they were making a huge profit and were well established on the American market, the company was able to make large investments, which would enable them to produce their own china quite independently.

The Civil War (1861-65) had disastrous effects on business. As nearly all their products were sold in the States, the company had to temporarily stop all their activities, in particular their building of the new factory and wait until the situation improved. Haviland Brothers went bankrupt so the factory in the Limousin area was left to fend for itself.

The French company Haviland et Compagnie (H et Cie)was officially founded on the 1st March 1864.

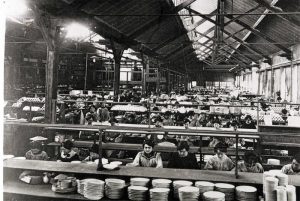

As soon as the war was over, Théodore (1842-1929) was sent to the USA. Although only 23 years old, he was a talented businessman and managed to develop a sales network which was very successful; the products of his firm became immensely popular, so much so that the factory in Limoges could not keep up with demand. Indeed in 1867 the export rate was 2872 crates – in 1870 it had gone up to 4767 and in 1872 it reached its peak at 5500, that is to say, it had doubled within five years. From that time on it was quite safe to start investing in new equipment. In 1870 the factory boasted 6 kilns and coal was used for the first time to heat them – this was a more modern technique which gave better results.

The family remained strongly attached to its religious beliefs; in Mary’s time nobody was allowed to wear clothes made of cotton because she disapproved of the work conditions of the black slaves. There were no Quaker communities in France so this is why the first generations of the Haviland family were not very active in their local parish (Limoges) although they did contribute financially. Regarding the welfare of their employees, however, it was quite a different story and in this they were similar to other protestant industrialists. In 1870 they started up a special fund to help soldiers and their families, followed later by a fund for mutual support, an association enabling employees to have access to what we would recognize as social housing today – they also started up a scheme for children’s holidays called A Key to the Countryside.

Finally, the independence of mind and respect of family conventions explain their membership in this particular branch of the Protestantism.

A new process of decorating

Charles Haviland became manager of the porcelain factory at an early age. Thanks to his father he had a large share of the American market and a totally new product on sale. His was the largest factory in France, perhaps even in Europe. However, porcelain is a luxury product, subject to changes in fashion. Charles realized that his production was old –fashioned. He needed new, original designs which could not be found in Limoges, where tradition was sacrosanct.

Now Charles undertook a daring commercial risk – he decided to contact a totally new kind of craftsman: Félix Bracquemond, an “artist” who was head of the workshop where china was hand-painted in the porcelain factory of Sèvres. He took him into his employment and made him “artistic director” of a workshop where new designs were thought up and then applied to china; it was situated at 116, Rue Michel Ange in Paris and was called the Auteuil workshop. Charles asked him to develop a new technique which would lower the cost price and to think up new exciting designs that were true works of art.

“Chrome lithography” is a process which makes it possible to apply a coloured design directly onto china and consequently it is not necessary any more for it to be hand painted so the production costs are considerably lower. New designs were set out according to the latest fashion of Japanese art; in addition new painting techniques just discovered by the Impressionists were also used. The result was hundreds of totally original styles of decoration which were very popular with customers.

In this way Haviland and Cie maintained the lion’s share of the market.

Art Nouveau and Art Deco

At the end of the 1880’s, Théodore returned from the States and set up his own company: “Théodore Haviland et Cie.” He built a modern factory and as there was a particularly large demand for china at that time, he was able to make it a thriving business, notwithstanding the already well established company Haviland et Cie. which was in the same area.

Tastes had changed once more – customers had had enough of Japanese art and they preferred traditional XVIIIth century designs: this consisted of flowers at the centre of a concentric decorative design. Théodore Haviland was quick to understand the significance of this change and a very successful policy was adopted: he presented his customers with a great variety of original designs – a new one came out every day! They were very elegant and he avoided the extremes of the “Art Nouveau” style.

William Dannat Haviland, son of Théodore, joined the firm in 1903 and became Manager in 1919 – it was now a very successful business. Once again, however, there were tragic events world-wide which had a negative effect on the market so he was forced to adapt to circumstances. He decided to continue the tradition of attractive domestic china with contemporary designs by the latest artists, so he in his turn engaged “artists” to decorate his china. In 1916, Edouard Marcel Sandoz designed a whole range of articles decorated with animals – their shapes were simplified in the extreme, almost cubist. William started to use two new products in the china-making process; celadon and ivory. His designs were typically “Avant Garde”, some even with the minimalist structure associated with “Art Deco”. He engaged a wide variety of artists, for example Jean Dufy and Suzanne Lalique (who had married his first cousin Paul Berty Haviland). His china is now recognized as being among the best that was made during the “Art Deco” period.

After World War II, the porcelain industry in Limoges went through hard times and the Haviland Society changed hands. It is however, still in business today.