The first wave: Foundation of many French churches

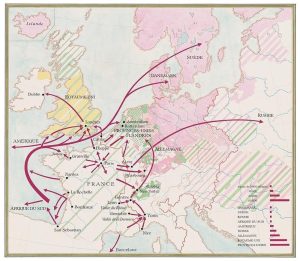

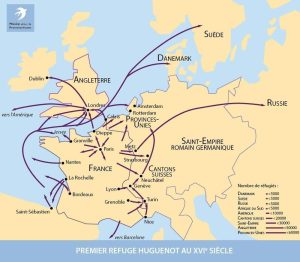

The first refugees arrived very early, right after the first persecutions. They came from the Atlantic coast, Picardy, Normandy, Brittany, Gascony. The accession of the very young king Edward VI (king from 1547 to 1553) sped up the process. Encouraged by his uncle, Protector Edward Seymour Duke of Somerset, and Thomas Cramer, then archbishop of Canterbury, the king granted his protection to the refugees. In 1550 he acknowledged the existence of the Church of Foreigners in London and consecrated it as an «established Church» equal to the Church of England. Prominent figures of the Reformation, such as Martin Bucer (1491-1551), were requested to come.

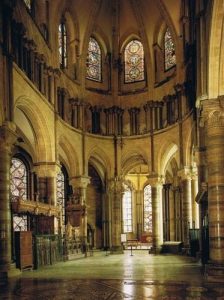

After an interruption during the reign of Mary Tudor (queen from 1553 to 1568), a Catholic princess very hostile to Protestantism and nicknamed «Bloody Mary», the Protestant Refuge started again under Elizabeth I (1558-1603). She offered asylum and protection to all who fled from persecution, especially those perpetrated by the Duke of Albe in the Spanish Netherlands. These refugees, along with the French-speaking Walloons, settled in communities around the churches they founded, as early as 1561 in Canterbury – where the Huguenot chapel can still be seen under the Cathedral – then in Norwich, Southampton and London. All of them were Calvinists. Between 1560 and1570 the estimated number of refugees was 6,000 – 7,000; they were craftsmen, and also engaged in trade, transport, food, but rural occupations were not represented.

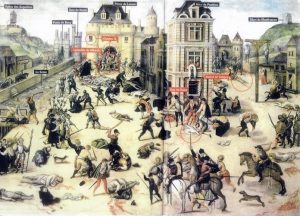

The feelings stirred by the Saint Bartholomew’s Day massacre (1572) were strong, the queen and court wore mourning clothes; the idea of forcibly converting children seemed particularly appalling. The Parisian tragedy precipitated a great increase in refugee numbers, especially from Normandy, and the consistory of the French Church had to add a weekly Sunday service at 7:00a.m.

After the Edict of Nantes, the number of refugees fell from 5,300 in 1573 to 3,500 in 1581 and to 1,500 in 1618, to rise again to 3,500 after the terrible years in La Rochelle. In the 1680s about 8,000 to 10,000 Huguenots found shelter in England, half of them in London, the other half in the Eastern part of the country. The second and third generations were assimilated into the Anglican Church. The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes provoked a more massive emigration wave.

The great Refuge

After the Revocation in 1685, 40,000 to 50,000 Huguenots found shelter in England, most of them from Normandy (25%) and Poitou (40%). They left via Bordeaux, La Rochelle or Nantes. The refugees were cared for by the communities created after the first Refuge. They had passports and they were granted some favours, such as equal taxes with the natives, but also equality of primary and secondary education for the children. The Reformed settled in large centres such as Canterbury but mainly London where there were up to 14 French churches in 1700. In London an alms house called “La Soupe” and a French hospital “La Providence” were founded in 1718.

In these particularly troubled times in English history, the influence of royal politics varied. For instance, Charles II – king from 1630 to 1681- facilitated Huguenot settlements and naturalisation, and even called for charity towards them. His brother James II – king from 1685 to 1688 – was a confirmed Catholic, but he was hostile to violence and held a moderate attitude towards French refugees – for instance he delayed publications about the Revocation and facilitated an attempt to settle Huguenots in Ireland.

It was not until his brother-in-law William III of Orange – king from 1689 to 1702 – invaded England and put an end to the Stuart dynasty, that the Protestant Faith was defended, and that French people of the Refuge came under his protection. In 1709 Queen Ann granted right of citizenship to all refugees settled in the country.

At the end of the 17th century an estimated 50,000 Huguenots had found shelter in England and accounted for 1% of the country’s population.

Contributions of the Refuge

As in all Refuge countries, the Huguenots made significant contributions to the host country. As merchants, manufacturers, craftsmen they were active in branches of industry such as silk, jewellery, haberdashery, paper. Architects, painters and engravers were busy adorning palaces and gardens.

The Huguenots were prominent in the financial sector but above all in the cultural sector, as freedom of the press was introduced in 1689. Several publications were the work of Huguenots: a pastor from the Perigord was responsible for the “Post-man” which was published three times a week and connected the Huguenot diaspora; the “Gentleman’s magazines”, as well as the “Postboy” were launched by Huguenots. Someone who lived in the Cevennes translated the work of the English republican John Locke.

The Refuge and international politics

The Refuge undoubtedly played a part in the rivalry between France and England at the end of the 17th century. William III of Orange came to power in England in 1689 thanks to the “Glorious Revolution”. His army was led by Frédéric-Armand de Schomberg, the Marshall of France, but of German origin, who remained faithful to Protestantism and had been allowed to leave France at the beginning of the Revocation. The same man, with an army of 3,000 Huguenots exiled in Holland, won the battle of Boyne in 1690 against the Irish Catholic Jacobites allied to Louis XIV. William was thus on the first ranks of Protestant belligerents confronting both French and Spanish Catholic power. Contrary to the absolutism of Louis XIV, the English crown asserted itself as a parliamentary monarchy.

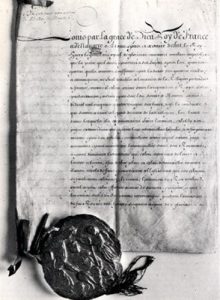

The French Protestant Church in London

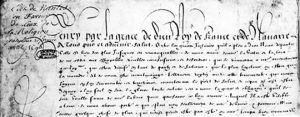

Edward VI had, on 24 July, 1550, signed letters patent recognising the “Stranger Church” in London. The appointment of pastors had to be approved by the sovereign up to this day. The Church included different nationalities – French, Dutch, German – which caused language problems; the French who went to another place of worship, in Threadneedle Street, where they stayed for 300 years. After the Revocation the flood of refugees led to the founding of about thirty churches in London and about ten elsewhere in the country.

Due to quick assimilation of the refugees many churches were to close. At the beginning of the 19th century only three French churches were left in London and a few in Canterbury and Brighton. The only French Protestant church currently left in London can be seen in Soho Square.