The assembly in Saumur

Philippe Duplessis-Mornay (1549-1623)

Philippe Duplessis-Mornay (1549-1623)

Duc Henri de Rohan (1579-1638)

Duc Henri de Rohan (1579-1638)

After the assassination of Henri IV in 1610, the future of the Edict of Nantes seemed fragile. The beginning of the regency by Mary of Medicis worried the Reformed community because of her alliance with Catholic Spain.

The representatives of the Protestant party held a political meeting in Saumur in 1611.

Those who were “cautious” along with Duplessis-Mornay advocated loyalty to the crown.

The hard liners led by Henri de Rohan advocated un confrontation.

The strategy of the confrontation prevailed in 1617 with the Béarn case but the division between the moderates and the hard liners weakened the Protestant party.

The Béarn case (1617-1620)

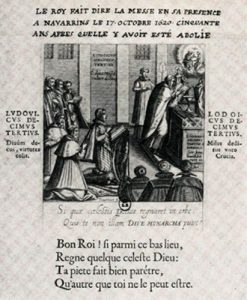

Restoration of Roman Catholic mass in Béarn © Bibliothèque Nationale

Restoration of Roman Catholic mass in Béarn © Bibliothèque Nationale

Henri IV had inherited the Béarn, a region that belonged to the d’Albret family, from his mother at the same time as of the kingdom of Navarre.

Thanks to Jeanne d’Albret’s willpower, the Béarn had become Protestant and the properties of the Catholic clergy had been confiscated. In 1599, Henry IV allowed Catholic worship again but the Catholic clergy had not been given back their properties.

In 1616, the Béarn council made up of Protestant magistrates had compromised themselves on occasions of social unrest stirred up by Protestant nobles. In 1617, the king’s council proclaimed the jointure of Béarn, a personal property of the king, to the kingdom of France and decided to have all the provisions of the Edict of Nantes implemented there. The Béarn council opposed this decision.

In 1620, king Louis XIII arrived in Pau with troops and replaced the Béarn council by a parliament where only Catholics sat. He restored Catholic worship. This change alarmed the Protestant party right across the kingdom and generated a movement of opposition to the king in the name of the Reformed “cause”.

The religious wars under Louis XIII

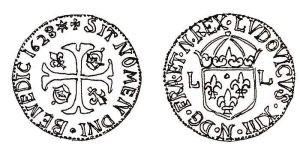

Rouanes, coins issued by the Duc de Rohan © Musée des Vallées Cévenoles

Rouanes, coins issued by the Duc de Rohan © Musée des Vallées Cévenoles

In these wars (also called the Rohan wars after M. de Rohan, the main leader of the Protestant party) the political power of the Protestants, which rested on political assemblies and strongholds, was at stake. The monarchy, on the verge of absolutism, could no longer stand a partisan minority that behaved as a “state within the state”.

Henri de Rohan stamped his own coinage, the “rouanes”, in Anduze : they were coins that looked like the king’s. In a letter dating back to November 1628, Henri de Bourbon blamed Henri de Rohan for “stamping coinage with royal arms when the king was the only one to be allowed to do so”.

First war (1621-1622)

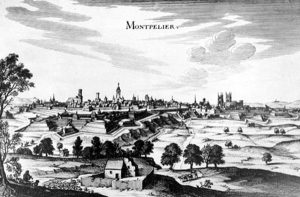

Montpellier © SHPF

Montpellier © SHPF

A national assembly of the Reformed churches was held in La Rochelle. It numbered 75 members, pastors or non-religious representatives, most of whom had connections with the main noble Protestant families. Many Churches had refused to send representatives. The assembly in La Rochelle protested against the annexation of Béarn, organised tax collections and soldier drafts and even appealed to the king of England for his protection.

As it refused to dissolve itself, the assembly looked as if it seceded, even though it claimed it was remaining faithful to the king and was only endeavouring to defend the freedom of the Reformed Churches.

The main Protestant leaders were :

- Henri de Rohan who was the leader in Languedoc

- Benjamin de Rohan, Lord de Soubise, who stayed in the area around La Rochelle

Louis XIII started a military campaign in April 1621 and easily took the two Protestant cities of Saumur and Thouars facing no resistance.

The city of Saint-Jean-d’Angely in Saintonge, held by Soubise, resisted but had to surrender after a two-week siege. Its walls were pulled down and it lost its privileges. The royal army headed towards and laid siege to Montauban which was defended by a strong garrison. But the army had to withdraw as it suffered a lot of losses on account of a flu epidemic.

Henri de Rohan was the leader in Languedoc. From 1621 to 1629, he set up his headquarters in Anduze which he turned into a stronghold (today one relict of the city’s walls still stands : the clock tower)

Soubise held La Rochelle which had acquired the maritime supremacy of the Atlantic coast and looted the Catholic cities in Lower-Poitou.

The king was called to their rescue and he fought battles in the Poitou marsh of Rié. Soubise lost several thousand troops and narrowly escaped himself. The royal army kept on gaining ground and besieged Protestant areas in Guyenne and ventured as far as Montpellier that was stormed but to no avail.

In October 1622, at the foot of Montpellier’s walls, the king granted the Protestants a treaty.

An amnesty treaty pardoned all the acts of war from 1621 to 1622. The Protestants had to dismantle numerous fortified sites and remove their garrisons from some of their strongholds. The king took Montpellier. The Assembly of La Rochelle accepted the terms of the peace treaty.

The second war (1624-1625)

Postage stamp depicting Richelieu and the siege of La Rochelle © Collection privée

Postage stamp depicting Richelieu and the siege of La Rochelle © Collection privée

The 1622 peace treaty of Montpellier was only a truce. At the beginning of 1624, the hostilities resumed when the fleet of La Rochelle pushed its way into the harbour of the Blavet River, near Lorient. Soubise confiscated all the vessels that were present in the harbour. At the beginning of 1625, he took control of all the ports on the islands of Ré and Oléron off the coast of Charentes.

In 1625, the king’s council, of which Richelieu had become a member as a minister in 1624, launched three expeditions :

- around Castres,

- on the island of Ré where the king’s forces landed,

- at sea where La Rochelle troops were defeated in September 1625 off the island of Ré, which caused Soubise to seek refuge in England.

A reconciliation agreement was signed in 1626 thanks to the mediation of the English. Louis XIII maintained the “privileges” the Protestants enjoyed from the Edict of Nantes but forced La Rochelle to accept the presence of a superintendent to control the city’s council.

The third war (1627-1629)

Montpellier © SHPF

Montpellier © SHPF

In 1627, England claimed they would protect French members of the Reformed Church. From March 1627 onwards, the duke of Buckingham prepared a naval expedition against France with over 80 vessels and 10,000 men. He was accompanied by Soubise.

The inhabitants of La Rochelle were divided. The magistrates, notably the mayor Jean Guiton, wanted to remain faithful to the king but the city welcomed the English. The duke landed on the island of Ré whose citadel resisted.

A counter-offensive forced the English squadrons out of the area in October 1627.

From August 1627, Richelieu organised the siege of La Rochelle. The blockade was carried out with a twelve-kilometre fortified trench and a eighteen-metre levee made up of boat wrecks.

In March 1628, La Rochelle pushed back the royal troops. In May, the duke of Buckingham came back but refused to force the blockade and withdrew. Another English fleet came back at the end of September but withdrew unsuccessfully.

For his part Henri de Rohan, stuck in the Cévennes, could not send troops to the rescue. In October 1628, La Rochelle, worn out and starving, surrendered after over a year’s heroic resistance organised by its mayor. After the surrender, the city was strewn with so many dead bodies that the survivors could not find the strength to bury them. There were only 150 able-bodied soldiers left and 5,000 survivors among the inhabitants. It was a personal political success for Richelieu who had supervised the siege.

In Languedoc, Henri de Rohan was still resisting. In September 1628, he had started negotiations with Spain which had become an enemy of France. When they finally came to an agreement, the Spanish forces did not have the time to intervene before the royal troops, which were back from Italy, pushed through the Vivarais and took the stronghold of Privas, Ardèche. The inhabitants were massacred or chased away under order not to return and the city was burnt down.

This news forced the strongholds in Languedoc to capitulate. Louis XIII set up a siege of Alès (Gard), which surrendered in 1629. Henri de Rohan surrendered. He was allowed to go into exile to Venice.

The Alès peace treaty (1629)

With the Alès (or Alais) treaty, Louis XIII granted amnesty to the inhabitants of the city who keep their properties. Members of the Reformed Church could go on worshipping.

The Alès treaty was confirmed by the Edict of Nîmes that granted amnesty to Protestants but deprived the Protestants of their privileges : strongholds and political assemblies.

It put an end to a six-year civil war and sealed the death of the Protestant party.

Richelieu had the fortifications of the rebel cities pulled down : from then on, the Protestants could only depend on the “good will” of the king.