The various bodies (the consistory and synod-based system)

The local church was ruled by a consistory (which today is called the Council of Elders).

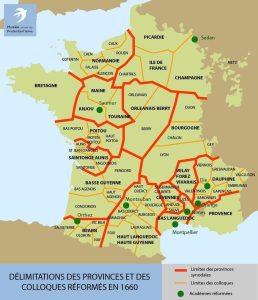

A certain number of local churches (as many as about thirty) gathered in a “colloque”, which today is called a consistory. The consistories addressed local issues.

At Provincial level, the Provincial Synod gathered several “colloques” and was summoned once a year.

At national level, the General Synod (today called National Synod) could not gather without the consent of the king and, from 1623, was called very irregularly. The last one was allowed in 1659.

The consistory

This body governed the local church and was made up of up of some tens or hundreds of families, (sometimes as many as 2 or 3,000 families : before 1628 the largest were Nîmes, Paris, Montauban, Dieppe, Caen and La Rochelle.

The members of the consistory were called Elders (today called the Council of Elders). There were about 10 of them, and the pastor took the chair. The Elders were appointed for 2 or 3 years but could be re-elected several times. They were chosen as men of good morals and of exemplary devoutness, with the consent of the congregation. There were few members by right : the Lords of the Manor in churches on large estates and the consul in Protestant towns.

The sessions of the consistory took place after religious services but their frequency varied from place to place.

The duties of the consistory

Its specific mission was to check if church rules were being enforced.

In each church the Elders visited the faithful, took note of any scandals, distributed tokens (“méreaux”) for the Lord’s Supper. The consistory tried to bring sinners to repent, either in public or within the privacy of their own home. If an Elder noticed a “scandal” (not worshipping, going to cabarets, comedies, dances, attending mass), he would report it to the consistory. They would then summon the culprit who was admonished and urged to repent. If he did not repent, he could be prevented from attending the Lord’s Supper (excommunicated).

Before each celebration of the Lord’s Supper (once every quarter), the consistory made a list of those who were forbidden to attend communion and they would not be given a token entitling them to receive it.

The consistory also settled quarrels between individuals and tried to reconcile the parties. In a very litigious century, it often managed to prevent cases from coming to court.

The Elders were also supposed to visit the sick. Every week, the Elders in turn took the pulpit, attended baptisms, weddings and burials. The consistory held the registers of births, marriages and deaths.

The finances of the Church were the responsibility the consistory : it had to raise fees and maintain the facilities (churches and parsonage houses).

The finances of the consistory

Each Church had to pay three permanent members : the pastor, the regent (the school teacher) and the caretaker, who rang the bell.

The main financial burden of the consistory was payment of the pastor who, at that time, remained in the same parish all his life. The amount varied from one parish to another and was fixed by agreement between the consistory and the new pastor. His housing and travel expenses to the daughter churches (if there were any), to conferences and synods, were paid. He was provided with a pension if he was too old and tired to remain a minister, and his widow and orphaned children were provided for if he died. Future pastors might need financial support while studying theology.

The wages of a school teacher were much lower, and those of a caretaker lower still. The consistory also contributed to the fees of the Deputy General to the court. It contributed (through the Provincial Synod) tothe financing of colleges and academies and, after 1660, supported religious prisoners.

Income was from the contributions of worshippers. The Elder for the district collected the contributions, usually every quarter.

Until 1620, a grant from the king (provided under the Edict of Nantes) was never given in full and ran out completely around 1620. In Protestant towns, a part of the budget was allocated to the Church.

Fortunately, there were numerous bequests and donations, as it was common for wills to include a legacy to the Church.

But many consistories ran into financial trouble and found it hard to pay their pastors.

Providing for the poor

Consistories were committed to help those in need, of whom there were many, especially when famine struck.

The consistory helped the sick, elderly, widows and orphans etc.

An Elder held the register of the poor and had to visit them every month to check whether they still needed assistance.

In some areas, there were Protestant doctors and hospitals to avoid the pressure exerted by priests in Catholic hospitals. Louis XIV stopped these in 1679.

The consistories helped poor children with their school expenses and apprenticeship fees.

They contributed to the well-being of prisoners and helped to buy back inmates who were reduced to slavery.

The "colloques"

They were made up of a number of local Churches and were a subdivision of a Province. Some provinces had only one “colloque” (Brittany and Provence) whereas others had as many as eight.

The “colloques” met between one and four times a year and consisted of a pastor and an elder for each church. The “colloque” settled disputes between churches or within a church when they had not been solved by the consistory. It might decide to punish or censor if necessary.

The royal commissioners

From 1623, “colloques”, Provincial or General Synods could not be held without the attendance of a Royal Commissioner. The latter would see that nothing being debated might harm the king or disturb public order.

At the beginning, this Royal Commissioner was Protestant, but, from 1679, he could be Catholic.

The Provincial Synods

The information comes from two sources : the rulings of the synods and the minutes of the Royal Commissioners.

The Provincial Synods met once a year. Then, until 1685, they met when the superintendent would allow it – once every two years, or even less frequently. A pastor and an Elder from each church were present.

As with every synod, the Provincial Synod opened with a sermon that the general public could attend. Sometimes there was a sermon every day. Each day began with prayer and the synod ended with a prayer.

The synod dealt with issues concerning the whole Province (obedience to the rules, children’s education, fast days…)

It settled issues that had not been settled by the “colloques” and appeals against decisions made by lower bodies of authority. It appointed the examiners for applicants to be pastors and admitted those who were considered fit for the job. It had to deal with finances of the churches (grievances of ill-paid pastors, churches in financial difficulty …)

It appointed delegates to the next National Synod.

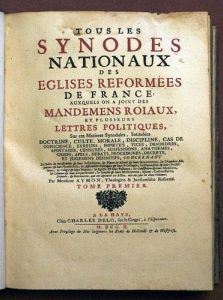

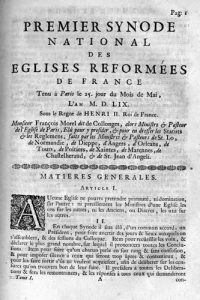

The National Synods

As the seventeenth century progressed, the more difficult it became to summon National Synods. From 1614, they could not meet without previous authorisation, and from 1623, not without the attendance of a Royal Commissioner. The commissioner was often appointed late and National Synods became less and less frequent.

Originally, they met every year, then, from 1598, every three years and finally, after1628, only four synods were held :

- in Charenton (1631),

- in Alançon (1637),

- in Charenton (1644),

- and in Loudun (1659).

Each Province sent four delegates, except Brittany and Provence which only sent two.

As a result, on average the synod was composed of 60 delegates – 30 pastors and 30 Elders.

After the opening sermon, the speech by the Royal Commissioner and reading of the Confession of Faith, the “Deputy General” read his report that had to be approved by the synod. The primary work of the synod was to read and review ecclesiastical discipline rules. The 40 articles laid down at the first synod in Paris in 1559 were, for a century, regularly revised and added to.

The synods were overwhelmed with the demands from individuals, pastors or churches and had to limit these. Then they wrote a list of complaints, which referred to the humiliations that members of the Reformed Church faced despite royal decrees. A delegation took this list to the king. Then the synods dealt with the general issues. For example, in 1623, they debated the theological disputes troubling the Netherlands and the decisions made by the synod in Dordrecht. In 1631, in Charenton, it was decided to allow Lutherans who wanted to, to attend the Lord’s Supper.

After the issues of general concern, the synod tackled those related to the Academies, their budget and the wages of the “Deputy General”. The accounts of the synods had really been simplified since the cancellation (around 1620) of the king’s grant, which had actually never been given in full. Previously the grant had had to be divided fairly.

Before dispersing, the synod checked the list of churches that were provided for and those which needed to be provided for, chose the city where the next synod was to take place, made a list of the pastors who had been removed, if necessary set the date of a general fast and finally read and signed the rulings of the synod.

After a final prayer by the synod moderator, the deputies took a copy of the rulings and returned to their Provinces.