The meeting of a small group of Protestants

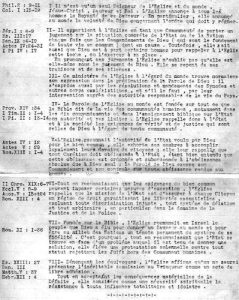

Theses of Pomeyrol © Collection privée

Theses of Pomeyrol © Collection privée

On 16 and 17 September 1941, without an official mandate, the Reverend Willem Visser’t Hooft and Madeleine Barot – secretary general of the Cimade – brought together a group of fifteen people at Pomeyrol (a meeting and retreat centre belonging to the French Reformed Church at Saint-Etienne-du-Grès, in the Bouches-du-Rhône region). Their aim was “to consider together what the church should be saying to the world”. The group comprised pastors, such as Jean Cadier, Georges Casalis (secretary general of the French Federation of Christian Students’ Associations), Henri Clavier, Paul Concord, Henri Eberhard, Jean Gastambide, Pierre Courtial, Jacques Deransart, Pierre Gagnier, Roland de Pury, André de Robert, André Vermeil ; and three lay persons, namely Madeleine Barot, Suzanne de Dietrich from Geneva, and René Courtin, professor at the Faculty of Law in Montpellier.

The meeting was an echo of the “theological Declaration of Barmen” in Germany (29-31 May 1934). When Hitler came into power, the regional Lutheran, Protestant, Reformed and United churches belonging to the Evangelische Kirch (Evangelical Church) were obliged to add the Aryan Paragraph and the affirmation of German supremacy to their constitutions.

On 29 May 1934, the synod in Barmen broke up, and Lutherans and Reformed united in one confessing church or bekennde Kirche. These rebels, from every part of Germany, protested against the subjugation of German Protestantism and the setting up of the Deutsche Christen (German Christians) organisation. Karl Barth was one of the main editors of the declaration which was presented as an exclusively religious act of spiritual resistance to defend the church and the purity of its message ; it did not specifically mention the persecution of the Jews. In spite of its shortcomings – which caused controversies after the war – its political meaning was obvious.

An act of resistance to Nazism

In France the text was published in the magazine Faith and Life headed by the Rev. Pierre Maury, and also in Social Christianity. The text of the Barmen declaration, along with those of the German pastor Martin Niemöller, was published in 1940 in the magazine Christian Witness, founded in Lyon. Upon the promulgation of the first antisemitic laws in the “free zone”, the need to create an ideological tool to resist Nazism led to the meeting in Pomeyrol.

The eight Pomeyrol Theses are “a theological reflection on the evangelical basis for a public statement of the Church”. The first four concerned the relationship between the state and the church, the fifth sets limits to obedience to the state, the sixth defined the respect of fundamental liberties, the seventh denounced antisemitism, and the eighth condemned collaboration. Thesis 7 was unambiguous : “a solemn protest against any law which places the Jews beyond human communities”. In Thesis 8 “denouncing ambiguities, the Church claims that inevitable submission to the victor should not be considered an act of free acceptance… and resistance to any totalitarian pressure and idolatry is considered a spiritual obligation”.

One recurrent theme throughout the theses was the relationship between the state and the church, including the right of the church to speak out publicly in the prevailing circumstances.

In spite of their relative caution, and of some violently hostile reactions, the Pomeyrol Theses were circulated by many pastors and students “former federationalists” who contributed to the establishment of a confessing mentality within French Protestantism, which is to say, the witness of the church ready “to pay the price of grace”, according to G. Casalis.