In France, there was general enthusiasm

Jacques Bossuet (1627-1704) © S.H.P.F.

Jacques Bossuet (1627-1704) © S.H.P.F.

The clergy celebrated the Revocation with public acts of thanks. In his funeral oration for Chancellor Le Tellier (January 25, 1686), Bossuet exclaimed :

« Poussons jusqu’au ciel nos acclamations et disons à ce nouveau Constantin, à ce nouveau Théodose, à ce nouveau Marcien, à ce nouveau Charlemagne (…) : Vous avez affermi la foi ; vous avez exterminé les hérétiques, c’est le digne ouvrage de votre règne… »

“Let’s cheer so loud that it can be heard in heaven and say to this new Constantin, this new Théodore, this new Marcien, this new Charlemagne : you have strengthened our faith ; you have exterminated the heretics, that is the praiseworthy work of your reign…”.

On October 28, 1685, Madame de Sévigné wrote to her cousin Bussy-Rabutin : “you must have seen the Edict with which the king repeals that of Nantes. Nothing is as beautiful as what it holds and never did a king do, or will a king ever do, such a memorable deed”.

In the midst of such praise, a few voices advocating discretion and moderation could be heard, such as that of the Jansenist Arnault in a letter to Mr. de Vaucel on December 13th, 1685 : « Je pense qu’on n’a pas mal fait de ne point faire de réjouissances publiques pour la révocation de l’Édit de Nantes et la conversion de tant d’hérétiques ; car comme on y a employé des voies un peu violentes., quoique, je ne le croie pas injustes, il est mieux de n’en pas triompher ».

“I think we were right in not rejoicing publicly over the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, and the conversion of so many heretics, because, since we resorted to violent means, which I think was not unfair, it is best not to boast about it”.

The only critical voices to be heard were those of Vauban in 1689 and, many years later, that of Saint-Simon. Vauban did not deny the legitimacy of the plan which was meant to bring about unity of the kingdom, but he took note of the various troubles which resulted for the State.

Memo from Vauban for the recall of the Huguenots

The Refugees shed their blood for the glory of their new country © S.H.P.F.

The Refugees shed their blood for the glory of their new country © S.H.P.F.

Governor of Lilles since 1684, then appointed lieutenant-general in 1688, Vauban sent Louvois a Memo for the recall of the Huguenots.

In this memo, he listed various troubles for the State resulting from the Revocation.

“Those eighty to one hundred thousand people of various backgrounds that left the kingdom who :

- took with them over thirty million pounds of in cash ;

- impoverished our arts and individual manufacturers, most of which were unknown to foreigners and drew tremendous amounts of money from various parts of Europe into France ;

- brought about the ruin of most of our trade ;

- increased the enemy fleets by roughly eight to nine thousand sailors, among the best in the kingdom ;

- increased their military by five to six hundred officers and ten to twelve thousand soldiers, many of whom were more seasoned than theirs, as shown on the occasions they have fought against us.

As regards those who stayed in the kingdom, we cannot say if a single one is a real convert since those that we thought were true converts often left the kingdom.”

Vauban felt sorry that not only had the industrialists, shop owners and craftsmen left, but numerous intellectuals as well :

« quantités de bonnes plumes qui ont déserté le Royaume (…) se sont cruellement déchaînées contre la France et la personne du Roi même. »

“numerous good writers that fled the kingdom (…) raged against the kingdom and the king himself”.

Along with others, Vauban feared that emigration might not simply represent a loss for the kingdom but also a gain for its enemies.

On the Protestant side

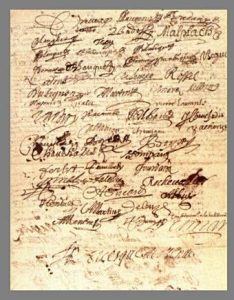

Renouncements in Marvejols © G996-Arch Dep Loz.

Renouncements in Marvejols © G996-Arch Dep Loz.

The issue of the Edict of Fontainebleau did not stop the “dragonnades” who carried on until 1686, with increasing violence. The Huguenots were terrified by this spread of violence. In the resulting anxiety some even began to wonder whether it was not a punishment from God.

The “dragonnades” were successful : numerous Protestants recanted. These were the “new converts”.

In Languedoc, Cévennes, Dauphiné, the announcement of the arrival of the dragoons and the stories of their cruelties, aroused panic and triggered mass recantations even before the dragoons did anything.

Many Protestants chose to leave the country despite the ban on doing so. Two hundred thousand were said to have escaped France and settled in the Protestant countries of Europe, also called the Refuge countries.

Many of the emigrants considered the Revocation as temporary and had planned a rapid return to France. This hope vanished with the Peace of Ryswick in 1697 and above all with the Peace of Utrecht in 1713.

Abroad

The Huguenot refugees are offered shelter in Brandebourg in 1686 © SHPF

The Huguenot refugees are offered shelter in Brandebourg in 1686 © SHPF

Many diplomatic protests were made to the king, and anti-French tracts circulated in the Refuge countries, especially in Holland.

The Protestant princes of Europe were shocked at the lot of the Huguenots.

In Brandeburgh, the Grand Elector did not hesitate to sever relations with Louis XIV.

In England, the Revocation undoubtedly paved the way for the accession of Prince William of Orange to the throne in the Glorious Revolution, removing James II whose intolerant absolutism roused fears among political leaders of a secret agreement with King Louis XIV in order to eliminate Protestantism in France.

Even extremely Catholic Austria condemned the methods used in France.

In Rome, even though the Pope, according to nuncio Ranuzzi, sent his blessing to the king for his “great work”, he disapproved of the use of force to obtain conversion.