Two evangelical tendencies emerged

The new ideas sweeping over France from 1520 onwards produced two trends of thought :

- the evangelical humanist trend, favourable to a reform within the Church ;

- the evangelical trend – referred to as “Lutheran” and influenced by the Reformation in Germany and in the towns of Switzerland – a trend that led to a break with the Roman Catholic Church.

Both ways of thinking often merged ; but because of their connexion with the Lutheran reformation, the humanist, evangelical ideas were likewise considered as a potential danger to the Church.

The humanist evangelical trend

Marguerite d'Angoulême (1492-1549) © S.H.P.F.

Marguerite d'Angoulême (1492-1549) © S.H.P.F.

Christians of a humanist tendency insisted on a return to the Gospel of Jesus Christ and to the original texts of the Bible. By his study of the Bible, Erasmus came to the conclusion that many rites and practices of the Roman Catholic Church were subject to criticism.

His innovatory ideas spread amongst educated circles and some of the higher members of the Church. They also reached the court of François Ier. Marguerite d’Angoulême, the king’s sister, encouraged the bishop of Meaux, Guillaume Briçonnet in his project of reforming his diocese. The bishop called Lefèvre d’Etaples to Meaux, where he founded the cenacle of Meaux and translated the New Testament into French. This drew heavy criticism from the Sorbonne, the theology university in Paris. Due to the increased popularity of « Lutheran » evangelical ideas, the parliament of Paris brought an action against the bishop of Meaux, accusing him of Lutheran heresy. They also forbade any translations of the Scriptures into French.

The « Lutheran » evangelical trend

Guillaume Farel (1489-1565) © S.H.P.F.

Guillaume Farel (1489-1565) © S.H.P.F.

From 1520 onwards, Luther’s writings were favourably received in France. Guillaume Farel, a member of the cenacle of Meaux, read them and spread their ideas. The Sorbonne forbade these writings in France since they were considered heretical. However, since they had been translated into French as early as 1524 and printed in Paris, Alençon, Lyon and especially outside France, they continued to be read secretly.

Thanks to Farel, who took refuge first in Strasbourg and then in Switzerland, the ideas of other reformers, notably Bucer and Zwingli, were introduced into France. But, from 1530 onwards, « heretical » ideas originated in Switzerland than France.

The Protestants, called Lutherans at the time, were members mostly of the social, literate elite : clerks, schoolmasters, students, lawyers, printers, men working in the book industry, craftsmen dealing with textiles and leather. Other sections of the population were won over to Protestantism by preachers and schoolmasters.

Protestants persecuted

From 1523 onwards the Protestants, considered as heretics, were penalised. The Sorbonne, the ecclesial authorities and Parliament imposed fines, sent them to prison, and monks and priests in particular were given a life sentence in prison or condemned to death at the stake.

The posters incident was a turning-point. These posters were put up everywhere in Paris, Orleans, Blois and even on the door of the king’s bedchamber. The posters violently denounced the catholic conception of the Eucharist and mass.

This violent gesture caused a split between the humanist and Lutheran evangelists. From now on, more repressive measures were taken, with the king’s agreement.

In 1546, in Meaux, 14 « Lutherans », including a pastor, were burnt at the stake. In the course of two years the Parliament in Paris, which governed the centre of France and Lyon, gave 500 people prison sentences ; and at least 68 of these were sentenced to death.

Such terrible suffering resulted in the return of some Protestants to Catholicism, but most of them were driven underground ; some, however, were even strengthened in their convictions.

The foundation of the protestant Church in France

Map of the Protestant minorities © S.H.P.F.

Map of the Protestant minorities © S.H.P.F.

From 1540 onwards, Calvin’s ideas, spreading from Geneva, began to deeply influence the reform movement in France.

The first protestant Church was in Meaux. It was only from 1555 onwards that other Churches were set up in different parts of France, notably in Paris, Angers and Valence. In some regions there were many Churches, for example in Provence, Languedoc and in the valley of the Garonne.

In 1559, the first secret assembly of representatives – both pastors and lay people – from the protestant Churches took place, forming the national synod of Paris. The synod was the link between local communities. In Paris, the synod delegates adopted a certain number of rules : a confession of faith and a structure of ecclesial discipline, both of which were inspired by Calvin. The organisation of the Churches was beneficial to the progress of the Reform movement throughout France.

The movement now spread from the social elite to the popular classes, especially in the towns where books and news spread easily. For this reason many craftsmen became Protestant.

A Protestant party

From 1555 onwards, many noblemen adhered to the Reformation, especially in the south of France, Normandy, Brie and Champagne. When Henri II died in 1559, a part of the nobility – all members by right of the king’s council – was Protestant. They included :

- Henri IV’s parents, Antoine de Bourbon and his wife Jeanne d’Albret,

- Antoine’s brother, Louis de Bourbon, prince of Condé,

- Gaspard de Coligny.

The fact that more and more people – including members of the nobility – joined the Reform movement, made the latter come out into the open and adopt a more political attitude. Members of the Reform movement wanted it to be legally recognized and wished it to have an active role in the running of the State. The nobility of the royal court hoped they could apply political pressure in favour of the protestant cause.

Events leading to the wars of religion

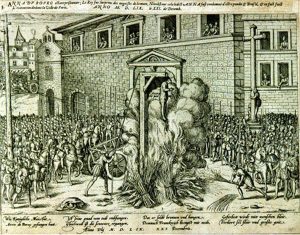

Death of Anne du Bourg (1559) © Musée Calvin de Noyon

Death of Anne du Bourg (1559) © Musée Calvin de Noyon

King Henri II had some well-placed and ambitious catholic noblemen at his court, notably François duke of Guise and his brother, the cardinal of Lorraine. When he died in 1559, the Guise family was powerful, to the detriment of the young king François II. In 1559, they ordered a man called Anne de Bourg to be hung and burnt at the stake on Grève square – he was a priest and a judge in the Paris parliament. Henri II had already arrested him because he had intervened during a special plenary session of parliament, referred to as “mercuriale”, where members could voice their complaints. He had pleaded for an end to the persecution of the Protestants.

In 1560, some protestant noblemen wanted to abduct the young king François II, to shield him from the influence of the Guise family. This plot, referred to as the Amboise conspiracy, failed. The Guise family took their vengeance by ordering a great number of executions, while the Protestants revolted in different places throughout France, seizing catholic Churches and holding Protestant services in them.

Catherine de Medici, who was Henri II’s widow and the regent of France in 1560 after the death of François II, feared the power of the Guise family. She did not want trouble with the Protestants, as she hoped for reconciliation between the two religious factions.

In 1561, she summoned Catholic and Protestant theologians to a colloquium at Poissy, in an attempt at reconciliation, but no common agreement was found.

In order to bring an end to the rapidly spreading Protestant movement, the triumvirate François, duke of Guise, the constable of Montmorency and Marshal Saint André took an oath on Easter Day 1561 to do away with Protestantism and never to tolerate any service of worship in France other than the Catholic mass.

The chancellor Michel de l’Hospital tried to convince the regent to grant Protestants the rights given by the Edict of January 1562, allowing them to hold services in the outskirts of towns and in the countryside. Protestant public worship would be made legal. But in fact, the edict did not bring satisfaction to either party because it came too late to appease them. Moreover, Charles IX lacked the means necessary for enforcing it.

The wars of religion were to begin after the massacre of Wassy.