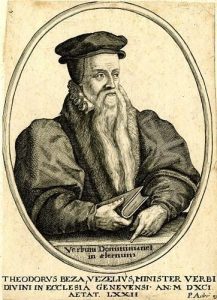

The life of Theodore Beza

He was born in Vézelay in 1519. When he was eight years old he was brought up by a tutor, Melchior Volmar, a Lutheran who taught him Greek, Latin and Hebrew. He furthered his studies in Bourges where he read Law. With Volmar he became an avid reader of the Bible, and was very impressed by a treatise of Heinrich Bullinger (1504-1575), the successor of Zwingli (1484-1531) in Zurich, who ‘made him discover true piety’ as he himself put it. Meanwhile he lived a joyful student life, deepened his knowledge of languages and wrote poetry.

In 1548 after he was ill, he converted to Protestantism, married and left for Geneva where he developed unbounded admiration for Jean Calvin. Pierre Viret requested him to hold the Chair of Greek at the Lausanne University where he often met with theologians and became a strong advocate of the Reformation.

He soon became a prominent figure in the world of the Reformation along with Jean Calvin, Farel and Viret.

He stayed in Lausanne until 1558 when he settled down in Geneva, where he taught theology and law. He became Calvin’s right-hand man.

In 1562, at the Colloquy of Poissy, Theodore Beza refused to compromise on the content of the last supper, and definitely refused any possible coexistence of the two religions within de Kingdom of France.

During the second war of religion (1562-1563) he was in Orléans as secretary of Prince Louis de Condé.

When he returned to Geneva he succeeded Calvin at the head of the Company of pastors upon the latter’s death in 1565. In 1580 he fell ill and gave up his role in the Company of pastors. He spent the rest of his life in Geneva and was devoted to theology, literature, history and poetry. He advocated the Reformed doctrine and promoted the organisation of Protestant Churches in France. He corresponded with Protestant princes to win the German States’ involvement in fighting the League.

He died in 1605.

The literary work of Theodore Beza

Beza produced works which remain in history for different reasons, such as his early poems written when he was a student, his youth writings in Latin poemata juvelinia, comprising light plays which were reproached to him throughout his life ; he also completed the translation into verse of psalms from the Huguenot psalter Clément Marot had initiated, and which were essential to the Protestant soul. His very conservative translation of the New Testament was meant to strengthen the Reformed doctrine. In 1580, he also published historical works, especially l’histoire ecclésiastique des Églises réformées. It was probably a collective publication reviewing the history of the Churches after accounts obtained from Reformed parishes of France.

The defence of Calvinism, Theodore Beza a theologian

In the 16th century, the Reformed Churches had the Roman Catholic Church in France as an adversary, and the Lutheran Church in the Holy Roman Germanic Empire as a competitor.

The former was supported by the Council of Trente and by the French Royal family, whereas the sovereigns of the great German States wished to bring all the Protestants together in their Church.

Beza strongly defended the Reformed standpoints on predestination and on the Last Supper against the Lutherans. But he was cautious because French Calvinists needed the money and the mercenaries from the German States and Swiss Cantons to resist in France.

At the Colloquy of Montbéliard, 1586-1587, he defended the Calvinist interpretation of the spiritual presence of Christ in the Eucharist opposed by Jacob Andrea, a Lutheran counsellor of the Duke of Wurtenberg, who stubbornly defended the real presence of Christ.

He left a great number of theological writings to defend what he considered to be the Truth of the Reformed dogma, not willing to grant any concession.

Political action, the conquest of France

As was said earlier, at the Colloquy of Poissy and with the Prince of Condé, Theodore Beza was not only a poet and a theologian but also a politician.

He organised the setting up of the Reformed Churches of France, the training of pastors, wrote a Confession of faith, a catechism enabling to understand the Protestant faith and to convince opponents. He insisted on the absolute need for discipline, consistories and synods.

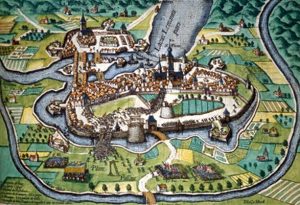

He untiringly exchanged letters with allies of the Reformation, namely with Swiss Protestant cities – Lausanne, Neuchâtel and Zurich-, and with German Protestant princes, to obtain funds and men to fight the League of Guise and sustain the Reformation in France. He also exchanged letters with Elizabeth of England’s entourage.

He established permanent contact with Henri of Navarre, who helped Geneva fight the aggressions of the Duke of Savoie during the Raconis war in 1582. Beza saw Henri of Navarre inevitably evolve from his role as the Protestant leader to that of the crown’s heir – the manifesto of Montauban 1586. Beza continued to intercede with his allies on behalf of Henri de Navarre and in 1587 he received the help of German soldiers and Swiss mercenaries, who were twice defeated by the Duke of Guise at Vimory and Auneau.

Henri IV’s conversion to Catholicism in 1593 came as a shock, but would not affect Beza’s loyalty to the King. The successive compromises of Henri IV with the Catholics heavily strained Beza’s loyalty, but he considered the signing of the Edict of Nantes in 1598 as a reward of his trust in Henri IV.

Overall assessment of Theodore Beza’s work

Theodore Beza was an intellectual and a man of action who established Calvin’s theology thanks to his defence of the Reformed ideas without flaw or compromise. He prepared and organised the conquest of a territory where his religion could be exercised. His dream of turning France into a Protestant country never came true, he died in 1605 at a time when the Edict of Nantes surely protected the Reformed in France.

He was undoubtedly one of those who worked most effectively to sustain the Reformation in Europe.