A liberal and a radical

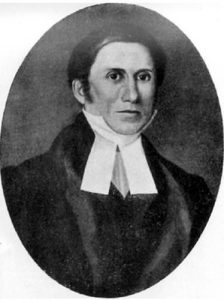

Colani was born in Lemé (Aisne) and received a pietist education in a Moravian Brethren community. He read theology in Strasbourg and began his ministry in the parish of St Nicolas ; he held the chair of Sacred Eloquence at the Theological Faculty.

His contacts with Scherer and the influence of Reuss had convinced him of the need to renew the French-speaking theological thought , in a such way as would make the Christian message more intelligible and acceptable to his contemporaries.

In 1850 he founded the Revuede théologie et de philosophie chrétienne (The Review of Theology and of Christian philosophy ), also known as the Revue de Strasbourg, which quickly became the voice of radical liberalism. Colani reproached orthodoxy – embodied in his opinion by the partisans of the Revival – with “failing to be a humanism and portraying God as soaring above the world, with taking into account neither the humanity of Jesus, nor the importance of progress in society” (de n’être pas un humanisme, de faire planer Dieu au-dessus du monde, de ne prendre en compte ni l’humanité de Jésus, ni les progrès à l’oeuvre dans la société). He would remove from the New Testament all passages that attributed to Jesus qualities not belonging to this world (his eschatological role) ; he considered that religious statements are meaningless unless the subject lives by them and for them (in Les Protestants by A.Encrevé 1993).

These opinions prompted heated polemics (cf.The time of divisions). The evangelicals reproached Colani with building his Christology on the sole ground of morals and conscience and with “doing away with the fundamental uniqueness of God’s call to man in Jesus Christ” (de supprimer le fondement du caractère unique que présente l’interpellation divine addressee à l’homme en Jésus-Christ). They set up their own journal, La Revue Chrétienne (The ChristianReview) in 1854.

After 1871, Colani gave up all his pastoral and professorial activities. In 1877 he became assistant-librarian at the Sorbonne ; and with a growing interest in literary and political issues he wrote for various newspapers (Le Temps, and Gambetta’s La République Française). At the 1872 General Synod of the Reformed Church his speeches in favour of the Reformation and of its spiritual heritage – in his opinion more or less neglected by protestant orthodoxy – drew attention, as well as his total opposition to the Declaration of Faith as agreed on by the Synod.