His studies

Tommy Fallot was born in Ban de la Roche in Alsace in 1844. Pastor Frédéric Oberlin (1740-1826), had left a deep impression there and this is probably why Fallot soon came to admire the men of faith mentioned below, who cared about the social issues arising from modern industrialisation and a new social group, the proletariat :

- Daniel Le Grand (1783-1859), his grandfather, an industrialist in Ban de la Roche.

- Christophe Dieterlin (1818-1875), another industrialist, but especially a “man of God”, who felt deeply that the message of the Gospel was first and foremost for the suffering and the poor, whatever their affliction.

Tommy Fallot started his theology studies in 1871 at Strasbourg university in a faculty which had been taken over by a German administration ; he was put off by their intellectual approach and the title of his thesis at the end of his studies in 1872 was The Poor and the Gospel : this was a foretaste of the priorities he would later have when he became a pastor.

The first years of his ministry

After four years as pastor of Wildersbach, near Ban de la Roche, he decided to leave the Lutheran Church and took up an appointment as pastor of the Free Church of the “chapelle du Nord (Boulevard de la Villette), a typically working-class area of Paris.

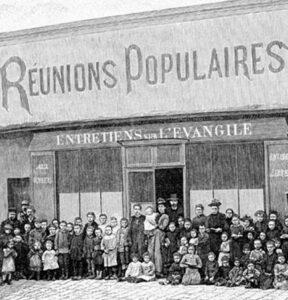

This is where he came into contact with the evangelization work of Reverend Robert Mac All, an British pastor who gave “moral lectures” which were intended to bring the Gospel message to the very poor.

These meetings were as successful as those of the Réveil, a great revival movement of faith which spread throughout Europe in the XIXth century.

Mac All asked Fallot to be responsible for the La Villette “station” and this lasted for 5 years, together with his ministry in the “chapelle du Nord”. However, Fallot soon came to realize that this rather emotional kind of evangelization had a major drawback : as it veered further and further from theological and Church issues, the result was that Protestantism became even more divided than before.

His social and political commitment

From 1882 onwards, in addition to his pastoral ministry, Fallot strove to defend public morality and one of his main aims was the problem of prostitution.

After having met Joséphine Butler (1828-1906) in 1869, who had fought a fierce battle against this scourge in England, he created the French League for the revival of public morality, which was as popular in the provinces as it was in Paris.

In fact he became more and more involved with the sufferings of the poor and this led him to take a greater interest in socialism, although he rejected its revolutionary aspect.

« I have been saved by my socialism » he wrote to a friend in 1892, although he disagreed strongly with the « class hatred » preached by leaders who « dreamed of revenge and conquest ». As he rejected political socialism, Fallot founded the Socialist circle of free Christian thinking, which became in 1882, the Society of mutual support and social studies, which was the basis of a great movement of Social Christianity, a somewhat idealistic project which criticized social injustice and strove to bring a Christian solution to such problems.

Fallot’s commitment drew to his side some most distinguished people in support of his cause, such as the dean Raoul Allier, the pastors Charles Wagner, Wilfred Monod and Elie Gounelle, but he met with little encouragement from the conservative and bourgeois ranks of Protestantism.

He was a pastor in the Drôme

In 1890, Fallot asked for a small parish in the countryside because his health had been affected by 12 years of intense activity. He was also weighed down by the fact that his socialist ideas were not at all well received by institutional Protestantism, where there was a marked division between orthodox and liberal believers.

In Sainte Croix, then in Aouste near Crest in the Drôme, he spent the last 10 years of his life actively evangelizing the local area.

He also spent much of this period writing about his two main sources of interest, on the one hand, ecumenism, although at that time the word did not exist, and on the other hand, the necessity of uniting the different tendencies which existed within the Eglises Réformées.