10 / 21

26 November 1580: Treaty of Fleix

10 June 1584: Death of the Duke of Anjou. Henri de Navarre became heir to the throne

September 1584: Formation of the second league

17 January 1585: Treaty of Joinville between the Guise and Philip II

31 March 1585: Proclamation of the ‘Offensive and Defensive Saint League’

7 July 1585: Treaty of Nemours imposed on Henri III, who revoked the previous edicts

1586: Success of Anne de Joyeuse in the South-West

20 October 1587: Defeat of royal troops at Coutras

Oct-Nov 1587: Victory of Duke of Guise over the Germans in Vimory (26 October) and in Auneau (24 November)

1587: Creation of a commoners’ league allied to that of the Princes

9 May 1588: Henri de Guise entered Paris

12 May 1588: Signature of the Edict of Union confirming the treaty of Nemours

23 December 1588: The duke of Guise was assassinated in Blois

24 December 1588: The Cardinal of Guise was assassinated. Unrest in Orleans and Paris

5 January 1589: Death of Catherine de Medici

30 April 1589: Bringing together of the two Henris at Plessis-Les-Tours

2 August1589: Henri III assassinated by Jacques Clément.

Henri de Navarre became King Henri IV

21 September 1589: Victory of Henri IV in Arques

October 1589: Siege of Paris

14 March 1560: Victory of Henri IV in Ivry

May-September 1590: New siege of Paris 1591 in the hands of the leaguers and the Duke Charles de Mayenne

1592: Campaign of Normandy

25 July 1593: Recanting of Henri IV in Saint-Denis

27 February 1594: Henri IV crowned in Chartres

22 March 1594: Henri IV entered Paris

30 April 1598: Edict of Nantes

Peaceful times

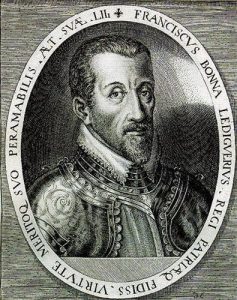

Henri de Lorraine, Duc de Guise (1550-1588) © S.H.P.F.

Henri de Lorraine, Duc de Guise (1550-1588) © S.H.P.F.

François de Valois, Duc d'Alençon, 1572 © National Gallery of Art - Washington

François de Valois, Duc d'Alençon, 1572 © National Gallery of Art - Washington

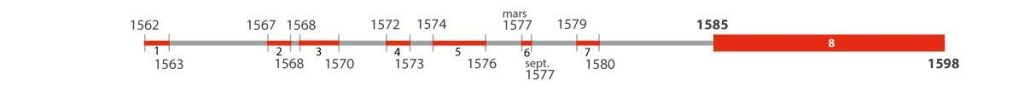

The eighth war of religion was often termed the battle of the three Henris, namely Henri III, Henri de Guise and Henri de Navarre. The latter won thirteen years later.

On 10 June 1584 upon François d’Alençon’s death, the Duke of Anjou and last brother of the King, Henri de Navarre, became the legitimate heir to the throne. The prospect of a Protestant on the throne of France prompted the forming of the second league or ‘holy union’ of Catholics, whose chief was Henri de Guise ‘Scar-face’. He was accompanied by his two brothers, Charles, Duke de Mayenne and Louis, the Cardinal Archbishop of Reims. Henri de Guise prepared himself. He signed the Treaty of Joinville in January 1585 with Philip II -who was afraid Henri III might support rebel Calvinists in the Netherlands- thus securing financial support.

In March 1585, he proclaimed the ‘the offensive and defensive and perpetual Holy League…for the defense and conservation of the Apostolic Roman Catholic religion, and the extirpation of heresies.’ The heirs to the heretics of the Bourbon family were excluded from the throne, Cardinal Charles de Bourbon -brother of Antoine and Louis I, prince of Condé- was announced as the only candidate under the name of Charles X. The announcement triggered the eighth war of Religion.

Times of War

Henry III © Collection privée

Henry III © Collection privée

Anne Duc de Joyeuse © S.H.P.F.

Anne Duc de Joyeuse © S.H.P.F.

The League took over the North of France. Cities in the South of France, such as Bordeaux and Marseilles, remained true to the King. Duke Henri de Guise imposed on Henri III, then isolated in Paris, the signing of the Treaty of Nemours on the 7th of July 1585. The ensuing Edict was registered by the Paris Parliament the following day and disavowed the civil tolerance policy. It restricted not only the freedom of worship, but also the freedom of conscience. It stated that Calvinists had to choose between recanting and exile within six months, that pastors were banished and stronghold towns were to be given back. The King of Navarre (Henri IV to be) was officially disinherited from the throne, which was reinforced by a Papal bull of Sixtus V. The League princes received big allowances and stronghold towns.

Battles started again. Henri de Navarre kept provinces in the Midi. He received support from Elizabeth I and the Protestant princes of Denmark and Germany. He proclaimed that their armies were not opposed to the King, but to the tyranny of de Guise. Royal military operations under Duke Anne de Joyeuse in the South-West entailed renewed violent actions. Prisoners’ executions and slaughter were glorified by Catholic preachers. But, at the battle of Coutras on the 20th of October 1587 the royal army led by Duke Anne de Joyeuse (who died there), was defeated. Henri III had the body given back to the family and attended a Mass in honour of the deceased enemies.

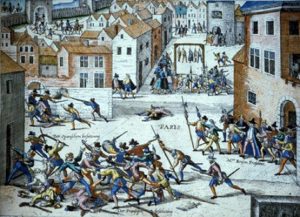

Journées des barricades en 1588 © Collection privée

Journées des barricades en 1588 © Collection privée

Henri de Lorraine, Duc de Guise (1550-1588) © S.H.P.F.

Henri de Lorraine, Duc de Guise (1550-1588) © S.H.P.F.

In Paris a commoner’s league was created and joined the League of Princes. Middle-class people organised themselves under leaders of the movement called ‘the sixteen’ referring to administrative divisions. Lampoons and pamphlets to the glory of the Guise were plentiful. The royal power was questioned.

On the 8th of February 1587 the execution of Mary Stuart, Queen of France and then of Scotland, a cousin of the Guise, symbolised the inhumanity of the Reformation. The act launched inflamed preachings, accusing the King of being Elizabeth of England’s accomplice. While Henri III had forbidden Duke Henri de Guise to come back to Paris, the latter came back to the city with his troops posted in every sensitive point.

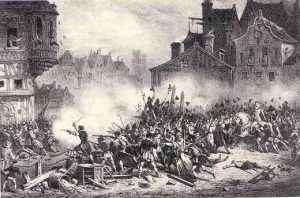

The Parisians were panic-stricken, afraid of a counter Saint Bartholomew Massacre. To defend itself the city rose up, and it was ‘barricades day’ (12 th of May 1588). The royal troops were stopped by the crowds, the Swiss guards were massacred, and the league members controlled the city. Henri III, humiliated, took refuge in Chartres and signed the Edict of Union on the 15th of July 1588, which confirmed the measures of the Edict of Nemours. Duke Henri de Guise was appointed lieutenant general of the royal army. The most extreme Catholics prevailed.

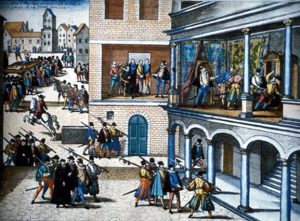

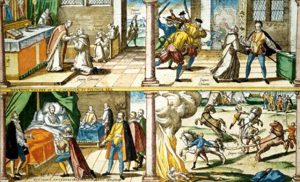

Assassination of the Duc de Guise (1588)

Assassination of the Duc de Guise (1588)

Charles de Lorraine (1554-1611) Duc de Mayenne © Collection privée

Charles de Lorraine (1554-1611) Duc de Mayenne © Collection privée

The promised meeting of the General Estates was held in Blois. On the 18th of October 1588, in front of the representatives of the three orders, subjugated by the members of the league, the king receded and took the oath to follow the Edict of Union to abolish heresy. Members of the league managed to make the king admit the incredible notion that religion was above the Salic Law to choose his successor. But in his pronouncement the King also warned the members of the League that far from reinforcing Catholicism, they endangered it through their factitious schemes. Thus, after he had remodeled his government, the King decided to « behead » the League, a party he deemed dangerous for the monarchy and for peace.

On the 23rd of December 1588, in the Castle of Blois, the Duke of Guise summoned by the King was stabbed by the ‘Forty Five’ King’s guards. His body was cut up in pieces and thrown into the fireplace, so that there were no relics of the martyr. The Cardinal of Guise was executed the following day, and the members of the Guise family arrested.

News of Duke Henri de Guise’s death immediately spread. On the 24th of December 1588 Paris took up arms. On the 7th of January 1589 the Sorbonne proclaimed the ‘tyrant king’ deposed. Outward signs of monarchy were destroyed, images of the king slashed.; black magic was used and pins were driven through his effigy. Collective purification prayers and penitent marches gathered the population in order to restore religious unity and remove the stain of heresy. Henri III was no longer the King of France but a tyrant. The Sorbonne unbound the people from their oath of fidelity to the King, some even advocated killing him. The representatives in the Paris Parliament who had remained faithful to the King were insulted and arrested. Duke Charles de Mayenne was appointed lieutenant general by the members of the League. This attitude against the royalty, claiming that popular consent makes the king, was an ideological shift. Indeed, the members of the league were taking over the ideas of the monarchomaques of previous years, whereas the Protestants conversely stood for monarchy by divine right and the succession rule.

Philippe Duplessis-Mornay (1549-1623)

Philippe Duplessis-Mornay (1549-1623)

Agreement between Henri III and Henri of Navarre (1588) © S.H.P.F.

Agreement between Henri III and Henri of Navarre (1588) © S.H.P.F.

Assassination of Henri III by Jacques Clément

Assassination of Henri III by Jacques Clément

Henri III left Blois and took shelter in Tours. Most big province towns, except for Bordeaux, Rennes and Loire valley cities, were in the hands of league members. Henri III approached the King of Navarre whose troops were as far up as Poitou. The latter sent Philippe Duplessis-Mornay to sign a truce with Henri III, a treaty made public on the 19th of March and registered by the Parliament. The Huguenots were granted freedom of worship in places they inhabited, and promised to give the king the cities they would seize. On the 30th of April both Henris met in Plessis-les-Tours and the crowd welcomed them to ‘long live the kings’. Their armies were joined and numbered some 40,000 men strong. They marched towards Paris which had weak defenses. In Paris the inhabitants raged against their sovereign who had formed an alliance with the heretics.

On the 1st of August 1589 Jacques Clément, a monk of the league, attacked Henri III stabbing him in the abdomen. He died in the night after admitting Henri de Navarre as his successor while ordering him to recant and become a Catholic.

Charles de Lorraine (1554-1611) Duc de Mayenne © Collection privée

Charles de Lorraine (1554-1611) Duc de Mayenne © Collection privée

Henri de Navarre became king under the name of Henri IV, but had to conquer his kingdom. His Huguenot followers urged him to become king but keep his religion. Calvinist lampoonists became active supporters of the monarchic principle. In 1589 the new King issued a statement promising to change nothing in the religious matter, to limit Protestant worship to places where it already existed, and to set up a council to teach him about the Catholic faith. In return the lords had to take a fidelity oath, and admit him as their natural prince according to the basic laws of the kingdom. There were varied reactions. On the catholic side many public figures, namely important parliament members rallied to the new king, as ‘politicians’ they were hostile to the Guise and the Spanish, and were committed to the freedom of the Gallican Church, against the Pope. They wanted order back and the end of violence. Some requested the King’s conversion, while others left for their properties and waited. Some joined the League. The Protestants were confused.

Paris was still in the hands of the league members who celebrated the king’s killer, justified by terribly violent lampoons against the ‘crowned apostate of Satan’. To them the new king was the Cardinal of Bourbon, under the name Charles X. A general council of the union was set up with Duke Charles de Mayenne, the last of the Guise brothers. The council prepared a true counter-state, awarding itself all powers, especially appointing the police and levying taxes. The council acknowledged league organisations created in most province towns. Ruled by local figures, they maintained some autonomy. They were violently opposed to royal troops, even provoked terror as in Marseilles. Their independence went as far as drafting a Union of the South with the Lyon and Provence regions.

But the League was not really united. A lot of nobles were cautious of associations led by upper middle-class lawyers, traders and speculators. The rivalries also existed between leaders, as many were opposed to the increasing authority of Duke Charles de Mayenne, lieutenant general of the League.

In the years 1588 and 1589 Henri IV increased military action in Normandy and around Paris. He won over Charles de Mayenne at Arques, near Dieppe, on the 21st of September 1589, and the royal troops made up of Protestant and Catholic contingents, besieged Paris, which resisted again.

Henri IV meets with Sully injured after the Ivry battle (1590) © S.H.P.F.

Henri IV meets with Sully injured after the Ivry battle (1590) © S.H.P.F.

The famous battle of Ivry near Dreux on the 14th of March 1590, led the way to a renewed siege of Paris, that lasted six months. Though the Parisian militias were some 50,000 men strong, the inhabitants were anxious. Exalted preachings and spectacular processions of armed monks were constant, and encouraged by the Papal Legate. Psalms of repentance were sung to obtain divine protection. The blockade of the city was total, thus the situation of the Parisians worsened daily, hunger and illnesses killed about 30,000 inhabitants. But the Spanish troops of Alexandre Farnèse Duke of Parme, intervened, obliging Henri IV to stop the siege in 1590.

In the night of the 20th and 21st of January 1591, he tried to trick his way into the city, sending soldiers dressed as flour traders, but he failed and it was called the ‘Day of flours’. In the city priests maintained an excited atmosphere by insulting the king. An atmosphere of terror prevailed with ‘political’ executions ordered by the council of the Sixteen, for instance Brisson, the first president of the Parliament, was accused of tepidness and hanged. The ‘furious’ in the League dreamt of a new Saint Bartholomew Massacre. Abuses stopped when Duke Charles de Mayenne returned, because he eradicated the most furious. In that period Cardinal of Bourbon, the league’s king Charles X, prisoner of the royalists, died on the 9th of May 1590.

François de Bonne, duc de Lesdiguières (1543-1626) © Wikipedia Commons

François de Bonne, duc de Lesdiguières (1543-1626) © Wikipedia Commons

Henri IV abandoned the siege of Paris and returned to Normandy. He failed to get Orléans and Rouen back, where the people were fanaticized by preachers. He sent an army to keep the way to the Netherlands free, and another one to stop Duke of Mercoeur and his Spanish allies from leaving Brittany. He was repeatedly defeated by Charles de Mayenne, helped by Spanish troops, at Aumale in February 1592. An English contingent came to help the king, but was put to the sword. Conversely on the Southern front, the Duke of Montmorency, was opposed to forces of the League and threatened the league-oriented Toulouse. In the South-East François de Lesdiguières was opposed to Charles-Emmanuel of Savoy. The General States of the League, summoned by Duke Charles de Mayenne, opened at the Louvre in late January 1593. But they had an incomplete view of the kingdom, as many royalist and Protestant provinces had not sent representatives, even more so as Henri IV had declared them illegal.

The king alone could summon the General States. Nevertheless representatives claimed that the basic law of the kingdom was not the Salic law, but the Catholicity principle, so that they had to choose a Catholic monarch. Spanish envoys tried to impose Infanta Isabella, Philip II and Catherine de Medici’s grand-daughter. Other descendants of the Valois were considered, such as Duke Philippe-Emanuel of Lorraine, Duke Charles-Emmanuel of Savoie, the new Cardinal of Bourbon (Charles son of the Prince of Condé, a first cousin to the king and nephew of the old cardinal who had just died) a Guise either Charles de Lorraine or also Duke of Mayenne.

Henri IV Abjuration Ceremony © S.H.P.F.

Henri IV Abjuration Ceremony © S.H.P.F.

Arrival of Henri IV in Paris in March 1594 © S.H.P.F.

Arrival of Henri IV in Paris in March 1594 © S.H.P.F.

But many parliamentarians refused to elect a foreign prince. Henri IV understood that he would never be accepted by the Catholics, and negotiations were initiated in May 1593 between representatives of the League and the king; hostilities were stopped. Henri IV confirmed his intention to recant and convert after being instructed as from July.

On the 25th of July 1593 in Saint-Denis, one of the high places of French monarchy, he did ‘the somersault’ and dressed in white satin pronounced his Catholic declaration of faith in front of the Archbishop of Bourges, who gave him absolution. In the following days, the king proclaimed a general truce and pardoned all those who had joined him. The French had not known peace for eight years. The Protestants assembled in Meaux from October to January 1594. They were worried. Henri IV promised to reinstate the 1577 Edict of Poitiers and the peace of Fleix. The Huguenots were allowed to worship everywhere, even at the Court, but discretely. It was not before the royal crowning at Chartres on the 27th of February1594 that the Parisians’ misgivings were dispelled.

Paris surrendered and opened its gates to Henri IV on the 22nd of March 1594. The Spanish left, the fanatical curates disappeared, the number of outcast was not over 140, most took refuge in the Spanish Netherlands. Decisions of the League authorities were abolished by the Parliament of Paris. Duke Charles de Mayenne was dismissed of his usurped office as lieutenant general of the kingdom. But no execution was ordered.

Until 1598, throughout the kingdom, Henri IV managed to get personal or collective support from his opponents thanks to many ‘reduction edicts’. The leniency of the king made rallying easier with amnesty and retaining league members , promoting some chiefs, ennobling public figures. Charles de Mayenne lost the government of Burgundy when he submitted, but he was given three stronghold towns where Protestant worshipping was forbidden.

Philippe de Lorraine, duke de Mercœur (1558-1602) © Collection privée

Philippe de Lorraine, duke de Mercœur (1558-1602) © Collection privée

Henri IV (1553-1610) © S.H.P.F.

Henri IV (1553-1610) © S.H.P.F.

Edict of Nantes (1598)

Edict of Nantes (1598)

In Languedoc, Henri de Joyeuse was appointed lieutenant general and Marshall of France. The rallying went along with huge financial generosities. ‘He got all of France for about 20 million pounds’ Eric le Roux wrote. Taxes would pay for these expenses, which explained anti fiscal uprising of peasants, the ‘croquants’ (‘yokels’), in the Midi. A total of about 700 league members, not pardoned by the king, found refuge abroad.

Then Henri IV only had to rid France of the Spanish whose troops had come to support the League and stayed in France. On the 17th of January 1595, the king declared war on Spain.

League oriented Burgundy, through which troops passed from Italy to Flandrers, was crushed after harsh battles. Members of the league in the South West rallied to Henri IV, who asked the young Duke Charles de Guise to submit Marseilles, then a self-declared Catholic independent republic, and François Lesdiguières to restore order in the Dauphiné opposed to Duke Charles-Emmanuel of Savoie.

There still was the Duke of Mercoeur (Philippe-Emmanuel de Lorraine) who was allied to the Spanish and threatened Nantes. His troops were engaged in armed robbery and abominations. He only submitted after being offered large sums of money.

On the Northern front, where the Spaniards ruled over many cities, Henri IV won the siege of Amiens thanks to the troops and financial support of the English and the Dutch. Peace was signed at Vervins on the 2nd of May 1598 thanks to the Pope’s mediation and meant the end of Spanish domination in Europe. Henri IV turned to ending the religious conflict by proclaiming the Edict of Nantes on the 30th of April 1598.

Huitième guerre de Religion (1567-1568)

Huitième guerre de Religion (1567-1568)