Civil peace, trust, religious unity

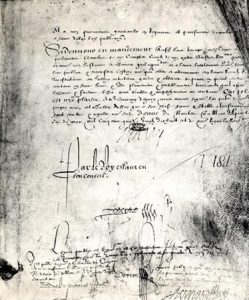

The Edict of Nantes: underwritings © S.H.P.F.

The Edict of Nantes: underwritings © S.H.P.F.

Registration of the Edict of Nantes by the Parliament of Paris © S.H.P.F.

Registration of the Edict of Nantes by the Parliament of Paris © S.H.P.F.

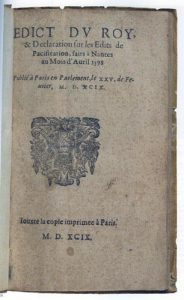

Edict of Nantes, publication of 1599

Edict of Nantes, publication of 1599

It was imposed by Henri IV with the immediate goal of achieving civil peace, and reinstating trust. He admitted that his ambition was religious unity in the kingdom. In the foreword, the King wished « to establish a good peace » enabling his « subjects of the Pretended Reformed Religion » to come back to the « true religion », his own, namely « the Catholic Apostolic and Roman religion. »

The Edict comprised four separate texts:

- the first letter patent promised an annual subsidy worth 45,000 ecus to ensure protestant worshipping, and to pay “ministers” called pastors;

- the Edict as such comprised 92 articles, was “perpetual and irrevocable”, i.e. it could not be modified except with a new Edict;

- a second letter patent ensured Protestants 150 refuge places for 8 years, 51 of which were stronghold towns with garrisons under Protestant rule;

- and 56 articles called “secret or particular” of lesser importance concerning local circumstances.

Some measures of the Edict of Nantes were advantageous for the Catholics, for instance mass was authorised everywhere including the Béarn region. Only Catholic worship was allowed in most cities. All buildings previously belonging to the Catholics were given back to them. Curates in parishes collected the tithe from the Protestants according to custom.

Other measures were advantageous for the Protestants, for instance granting them freedom of conscience, respecting synod organisation, regularising education, granting access to all public dignities and offices.

Protestant worship was limited. It was authorised only in some places. It was forbidden wherever it was not specifically authorised, notably at the Court, in Paris, and less than five leagues around the capital city, and also in the army. The Edict comprised general measures, such as a general amnesty – except in exceptional cases – , forbidding unrest, provocations, exciting people, equal rights in terms of law and justice, freedom to recant which meant changing religion, judicial guarantees thanks to mixed chambers, the right for immigrants and their children to return.

The Edict was registered by the parliaments. Some were extremely hostile, Henri IV for instance had to impose it to the Parliament in Paris, and in Rouen it was ratified only eleven years later.